Warwick

Monað modes lust mæla gehƿylce ferð to feran.

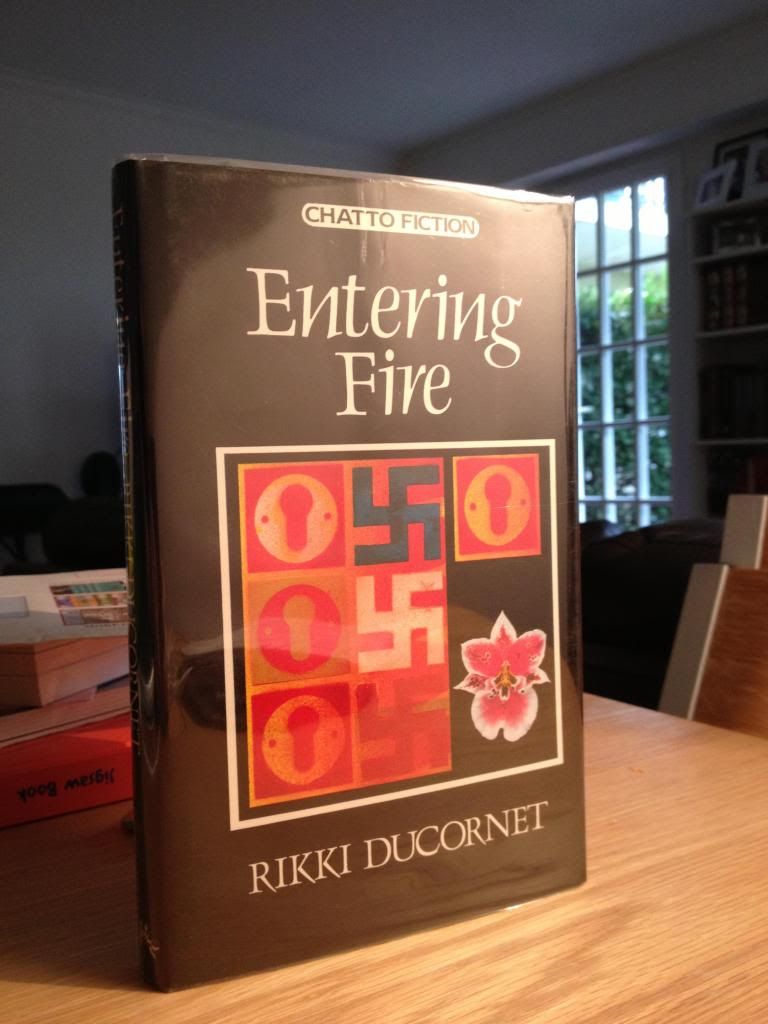

Entering Fire

Water has never been my element. Give me a hot wind. Give me fire.

The second in Rikki Ducornet's loose quartet of elemental novels, Entering Fire is a fantastic blend of high-level botany, extreme racism, tropical fevers and alchemy, all infused with the author's characteristically deep understanding of sexual instincts and behaviour.

Her first book was set in the Loire Valley; this one begins in the same place, but then rapidly expands to take in Occupied Paris, the Brazilian rainforest during the rubber boom, and the paranoia of McCarthyite America. Ducornet is showing off her range, and I liked it very much; there is something almost Pynchonesque in this sexy, dilettantish but deeply thoughtful approach to historical incident.

There are two narrators, father and son: two poles of humanity, two opposed visions of the male experience. The father, Lamprias de Bergerac – a descendant of Cyrano – loves women almost to excess (a trait to which we can note that Ducornet is always very sympathetic). Lamprias is world-renowned as ‘the Einstein of botany’, whose life, when he's not dallying in various exotic brothels, has been dedicated to the study of orchids – those plants known for their ‘impudent display of tiger-striped, peachvelvety, sticky and incandescent genitalia’. Yum!

The son, Septimus, is a nightmarish Céline caricature. A violent antisemite and misogynist, he welcomes the Nazis to France with open arms and contributes gleefully to the ensuing suppressions. Females, with the single exception of his mother, terrify and disgust him: ‘I like to imagine a brothel where the women – and each and every one of them has her feet bound – are infibulated when not in use and tied to their beds. That's my idea of Paradise.’

Septimus's voice is terrifying: he is a continuation of the Exorcist from The Stain, now fully gone over to the dark side. It is instructive, if uncomfortable, to read about the Nazi occupation from the point of view of a character so enthusiastic about it.

His father's narration, by contrast, is lush, verdant, polyphiloprogenitive – full of beautifully pullulating descriptions, such as this sketch of turn-of-the-century Rio:

Etched into my brain are visions of young, green Spanish girls sipping sherbet and preening like grebes on balconies, bouncy French whores nibbling pineapple and dealing out cards, English lasses floating past on imported bicycles and everywhere a European bustle of full skirts. Beneath the tropical sun the women sweated like mares – the odour of their overheated flesh was everywhere – their breasts pressed beneath the lace of their bodices like flowers in a book of verse. And now suddenly I remember the laundresses hanging out the city's wash to dry in the blazing sun. And camisoles and shifts and bloomers and petticoats. There were men in Rio, too, but I took little notice of them….

I mean come on. When Ducornet is in flow like this you feel that you can positively bathe in her prose. She has a tendency of coming out with things that I don't think would ever even occur to me and that I'd be scared to write down if they did: ‘Whores, like orchids, are the female archetype par excellence: painted, scented, seductive,’ she has her most sympathetic character say – but then immediately develops the maxim into something more nuanced:

Beneath their masks, the women of the Palace were fragile, luscious and unique. But the men who visited them were so blinded by lust they never saw what was there, only what was painted there.

Her style, as well as her scope, has developed since the first book: she is slightly more restrained here and more in control. Occasionally this can make her sound a little sententious – that sense of sheer fun has been toned down – but generally speaking, it feels more mature. And I was surprised to see the narrative enlivened by several excellent jokes (not something I'd previously imagined would be her forte):

You will understand why later, when Senator McCarthy asked me if my companion was a Marxist, I answered without hesitation, Yes. Of course, I was thinking of Groucho.

And don't even get me started on the insults – ‘Your mother has a cunt like a hippopotamus yawning’, anyone?

With its two oscillating narrators, the book will whisper to you on a symbolic level too, even if you're not always sure exactly what point is being made. And though Ducornet still sometimes takes herself just a smidgen too seriously for my taste, her sentences are a delight, a wonder, a pure pleasure. Rikki's world is stark and often frightening, but it's also full of sensual delights. I closed the book already craving the chance to spend more time there.

---------------------------------- Original non-review:

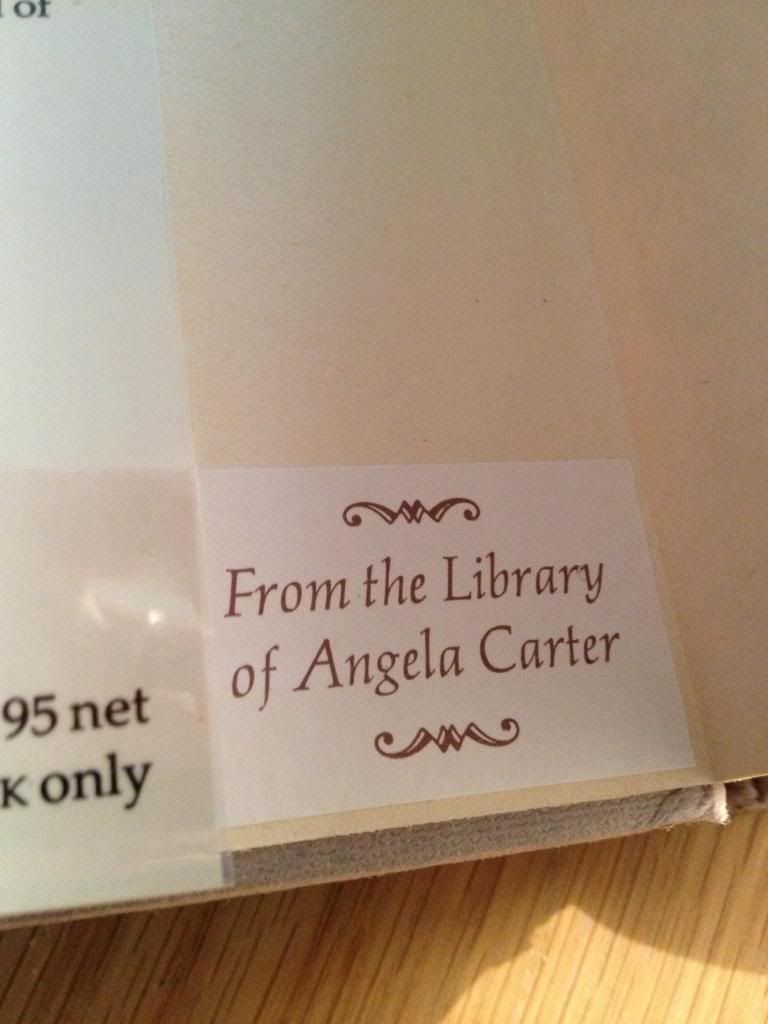

Prepare to be jealous. Not only do I have a first edition of Rikki Ducornet's Entering Fire, but I have Angela Carter's old copy.

:-D

1

1