Warwick

Monað modes lust mæla gehƿylce ferð to feran.

Homo Faber

And now here at last is a real book for grown-ups. Intelligent and utterly unsentimental, Homo Faber would, I feel, have been wasted on me if I'd read it ten years ago; now it strikes me as extraordinary. (This is unlike most novels, which, if not actually aimed at people in their late teens and early twenties, seem to resonate most strongly with that intense and exciting age group.)

As it happens, Walter Faber, the central character of this novel, does not read novels at all. He can't see the point. A technician for UNESCO, Faber builds things, records them, and analyses them. He believes in logic, reason, facts, brute statistics. A machine impresses him in a way that a human does not, because ‘it feels no fear and no hope, which only disturb, it has no wishes with regard to the result, it operates according to the pure logic of probability.’ Faber has few close male friends; women he can't relate to at all. Too emotional. ‘I'm not cynical,’ he explains. ‘I'm merely realistic, which is something women can't stand.’

I called her a sentimentalist and arty crafty. She called me Homo Faber.

His one serious relationship ended in divorce years ago. She scorned his beloved technology as ‘the knack of so arranging the world that we don't have to experience it.’ (And she, by contrast, was an archaeologist: ‘I stick the past together,’ she says in one of the novel's few moments of unsubtlety.)

I can imagine many readers finding Faber very unlikeable, even monstrous; and yet I feel desperately defensive towards him, perhaps because he reminds me of my father. Actually he reminds me of all fathers – there is an air of generalised daddishness about him, and this is not coincidental: the notion of paternity is crucial to the book.

‘I like functionalism,’ Faber says. He has a prose style to match. This is not to say that it is dry, or clunky, or unartful, because it is none of those things. The style is astonishingly telegraphic, elliptical, Faber narrating the facts that he considers important. The effect is staccato but wonderful; an extreme example here from a virtuoso section set in Havana:

My lust for looking.

My desire.

Vacuum between the loins.

I exist now only for shoeshine boys!

The pimps.

The ice-cream vendors.

Their vehicle: a combination of old pram and mobile canteen added to half a bicycle, a baldachin with rusty curtains; a carbide lamp; all around, the green twilight dotted with their flared skirts.

The lilac moon.

Often you are forced to read between the lines to understand what is really going on, and sometimes this reaches such a pitch that one has the impression of having experienced a scene twice. All the time Faber is writing to understand what has happened, and to justify his behaviour to himself. He can hardly accept the novelistic coincidences that the story involves: this cannot have happened. How was I to know. What else could I have done. The probability was minuscule. These were the facts as I knew them.

I am not mentioning the plot because it shouldn't be spoiled. Which seems strange, because we are given all the main facts quite early on. But part of the point of the book is discovering that the facts are not always, after all, the most important thing.

It's not often I really, really love books in translation. This is not because of any hipsterish misconception that you're not getting the "real" book, it's just that one of the things I most enjoy analysing when I read is the nuts-and-bolts mechanics of sentence construction and vocabulary choice, and this is all very different when you are reading the words of a translator. (Not that translators are not adept at this too – they are – but their motives and concerns are to do with fidelity to someone else's idea rather than their own, and this difference is fundamental.) But here I was riveted by the technique on display.

There is a moment where Faber recalls being on a beach in Greece with a girl. The two of them have a competition of similes: describing what they can see in terms of what it looks like. This is new ground for scientific-minded Faber, but he gets into it, and the paragraph rolls on for pages:

Then we found we could make out the surf on the seashore. Like beer froth. Sabeth thought, like a ruche! I took back my beer froth and said, like fibreglass. But Sabeth didn't know what fibreglass was. Then came the first rays of the sun over the sea: like a sheaf, like spears, like cracks in a glass, like a monstrance, like photos of electron bombardment. But there was only one point for each round; it was no use producing half a dozen similes. Soon after this the sun rose, dazzling. Like metal spurting out of a furnace, I thought: Sabeth said nothing and lost a point….

It's hard to describe the effect this long passage has on you, coming as it does after 150 pages in which I don't think a single simile had been deployed. To me it felt like being hit by a truck. It's one of the most unusual and powerful devices I can remember, in terms of constructing a novel, and the reason is that the passage coincides exactly with a moment of exquisite emotion both for Faber the character, experiencing it, and for Faber the narrator, remembering it. There is something technically brilliant going on in here.

There are so many other aspects to this superb novel that I haven't even touched on: its comments on the war, its deliberate and wide-ranging internationalism, its precise descriptive scenes. The story is clear-eyed and matter-of-fact and this has a cumulative effect that is quite devastating – heart-breaking, really. And yet for all that, what I am left with is this unexpected, life-affirming feeling…a renewed appreciation of what existence entails:

To be alive: to be in the light. Driving donkeys around somewhere (like that old man in Corinth) – that's all our job amounts to! The main thing is to stand up to the light, to joy (like our child) in the knowledge that I shall be extinguished in the light over gorse, asphalt and sea, to stand up to time, or rather to eternity in the instant. To be eternal means to have existed.

«Chuchichäschtli»

A mini-glossary of Swiss German, focusing mainly on the more picturesque or charming items of vocabulary. (To recap, Swiss German is not the same as Swiss Standard German, the form of German used in Swiss media, publishing and politics. Swiss German is a separate language altogether, though related.)

The booklet's title is probably the single most famous word in Swiss German, mainly because it's so notoriously difficult for non-native speakers to pronounce, and hence has become a kind of Swiss shibboleth. In standard German, those chs are either ‘palatal’ (/ç/, as in ich) or ‘velar’ (/x/, as in ach), depending on whether they come after a front vowel or a back vowel; but in Swiss German, they are all velar – indeed in many dialects, they are pronounced even further back in the throat, with the tongue right up against the uvula. The word means ‘kitchen cupboard’, and you can hear a couple of Swiss people saying it here.

One thing to note in Chuchichäschtli is that ending in -li, a very common Swiss German diminutive form which crops up in all their most ‘iconic’ phrases. I also note for example Chäferli ‘sweetheart’, or the even more delightfully economic Schmutzli, which means ‘Santa's little helper’.

To mention some others at random: we have the classically Swiss (Traichlä ‘cowbell’), the weirdly specific (Huscheli ‘an easily frightened woman’), along with the expected (Zmorgä ‘breakfast’) and the unexpected (Wobi ‘cow’ – where on earth does that come from?).

The wordlist includes German as well as English translations, which is useful for comparison. However, it's in no way a comprehensive dictionary and it does not include even basic information like noun genders. Still. As a personable sample of the language it's got its merits, and given the relative lack of literature on Swiss German, this booklet is a welcome introduction.

I thought this was incredibly charming and atmospheric, despite the fact that it's essentially the sort of simple religious allegory that normally makes me run a mile. The Christian symbolism is indeed the whole point: the author was a nineteenth-century village pastor who regarded his fiction as a kind of extended sermon. And yet his sense of pacing and the detail of his descriptions just make it such a pleasure to read for all kinds of unexpected reasons.

The bucolic early scenes of life in a tiny Swiss village are clearly written from experience, and I was just fascinated by the insight into daily life that's on show here. The way the maids tie their hair into bunches, how the old men light their pipes, how thickly the bread should be cut – lovely rich sense-pictures of all the kitchen activity:

Drinnen in der weiten, reinen Küche knisterte ein mächtiges Feuer von Tannenholz, in weiter Pfanne knallten Kaffeebohnen, die eine stattliche Frau mit hölzerner Kelle durcheinanderrührte, nebenbei knarrte die Kaffeemühle zwischen den Knien einer frischgewaschenen Magd […].

Inside in the big, clean kitchen a huge fire of pine wood was crackling; in a big pan could be heard the popping of coffee beans which a stately-looking woman was stirring around with a wooden ladle, while nearby the coffee mill was grinding between the knees of a freshly washed maid….

These are part of the preparations for a meal to celebrate a christening. The first course, incidentally, is a crazy local speciality that sounds like some sort of sweet-savoury mulled wine, yum:

…guten Bernersuppe, bestehend aus Wein, geröstetem Brot, Eiern, Zucker, Zimmet und Safran, diesem ebenso altertümlichen Gewürze, das an einem Kindstaufeschmaus in der Suppe, im Voressen, im süßen Tee vorkommen muß.

…good Bernese soup, consisting of wine, toasted bread, eggs, sugar, cinnamon and saffron, that equally old-fashioned spice which has to be present at a christening feast in the soup, in the first course after the soup and in the sweetened tea.

So if you ever have to celebrate a christening in Bern, now you know what to serve.

Anyway, I'm making this sound like a culinary textbook. It's actually an effectively creepy tale of Satanic possession – one that draws on that whole folkloric tradition of simple villagers making pacts with the Devil. There is much thunder and lightning and several dramatic set-pieces involving new-born babies, green huntsmen, evil knights, heroic priests, hideous deaths, and of course the anticipated variety of arachnean antics.

Having just read A Concise History of Switzerland, it was interesting to me that the story-within-a-story comprising the main part of this tale takes place in the sixteenth century, before this little patch of the Emmental had become fully part of the Swiss confederacy. One theme that emerges from Swiss history is the idea of different communities banding together to form self-governing political units, without the feudal overlordship that was the norm everywhere else in Europe. It's striking then that when this nineteenth-century villager is telling a story about the bad old days, he looks all the way back to when this little area was still a commandery of the Teutonic Knights, when the villagers had to bow their heads to the lord of Sumiswald Castle. Clearly this is secondary to the religious allegory on show here, but it adds a fascinating extra layer to the story.

And indeed, going through the original German text, even a beginner like me can see that it contains several specifically Swiss elements – local foodstuffs like Züpfe (translated as ‘Bernese cake’) or Hafermus (‘porridge’), as well as words like Meitschi ‘girl’, which is here given a comparably regional flavour by the translation ‘lass’. Actually the translation as a whole, from HM Waidon back in 1958 (reprinted in the 2009 OneWorld Classics edition), is wonderfully supple and readable.

Thomas Mann famously said that he admired The Black Spider ‘like almost no other piece of world literature’, and sure enough, although it really shouldn't be that interesting, somehow it seems to add up to more than the sum of its parts. I recommend turning the lights down and indulging in a copy for a literary, arachnophobic Halloween treat.

‘God is the opposite of Rodin.’

Imagine the school scenes from Gormenghast rewritten by Kafka and you'll have a good idea of the atmosphere of Jakob von Gunten, a short and stodgy philosophical fable of a very Germanic kind. It's easy to see why Kafka and Hesse were such fans; I wasn't quite so convinced, although I can understand why so many people love it.

The novel consists of a journal written by the title character, who has enrolled in a school for servants (based on Walser's own experience at a valet school in Berlin). The Benjamenta Institute is a closed world, with its own bizarre rules, a remote Principal, a mysterious Instructress – it's all dusty classrooms and intimations of impending disaster. In this constrained setting, Jakob conducts his own explorations of the interior world – probing his mind, examining his relationships with other people, and recording everything in a breathless, childlike narrative.

The microcosmic environment and the introspective narrator combine to produce a sort of parable about the importance of fully immersing yourself in everyday existence.

I pay attention, and that makes life more beautiful, for if we don't have to pay attention there really is no life.

However, this theme doesn't come without a certain ‘nativist’, anti-intellectual strain that I found a little disingenuous, however appealing. Jakob hates ‘the kind of person who pretends he understands everything and beamingly parades knowledge and wit’; what he likes is simplicity, people who simply do, without analysing. This is an awkward message for a writer to pull off, because a writer is precisely someone who reflects on and analyses their experiences. (And indeed for Jakob, writers are ‘just windbags who only want to study, make pictures and observations. To live is what matters, then the observation happens of its own accord.’)

Of course, Jakob himself has to embody exactly what he says he hates, otherwise he wouldn't be able to narrate a book. So he's intelligent and thoughtful, but he's not happy about it.

I despise my capacity for thinking. I value only experiences, and these, as a rule, are quite independent of all thinking and comparing. Thus I value the way in which I open a door. There is more hidden life in opening a door than in asking a question.

A really beautiful phrase – but the idea behind it, though attractive, with a little reflection seems obviously wrong. I say ‘obviously’ because if it were true, there would be no need to write books like this in the first place. If this book has any value at all, then that value can only be conveyed through means that the book itself disparages.

It has to be said as well that Christopher Middleton's translation (in the NYRB edition) seems rather heavy-handed and, well, infelicitous at times. We have sentences such as, ‘Schacht likes to offend against the rules and I, to be candid, unfortunately no less,’ which can only go through your head in a thick German accent. (Oops, I mean Swiss.) On the other hand, Middleton's introduction reads a bit awkwardly too, so maybe that's just the way he speaks.

Walser once said, ‘God is the opposite of Rodin.’ I don't know what he meant but I like it, and I didn't want to end this review without mentioning it somewhere. This book is similarly cryptic, provocative and anti-artistic. I wouldn't recommend it exactly, but if I saw you reading it in Starbucks I'd nod sagely and offer to buy you another pumpkin latte.

6

6

fiction

fiction

Reines de la France

A minor work from the terrifyingly multitalented Jean Cocteau, novelist, poet, screenwriter, artist, photographer, film director, et various al. My only previous exposure to his œuvre had been the proto-Surrealist ballet Parade, for which Satie had written the music and Picasso had designed the sets. (Those were the days!) Parade was so crazy it started riots; with that in mind, it was a surprise for me to read the carefully measured sentences and elegant judgements contained in this collection of micro-essays.

Although the title means ‘Queens of France’, the subjects are not all crowned royals, but rather Cocteau's pick of the queens of French culture, society, fashion and history. He starts with Saint Geneviève in the fifth century and works his way forwards to Anna de Noailles, spending just a couple of pages on each, and summing up what he sees as their intrinsically French, intrinsically female qualities.

It's an interesting format, and reminded me a bit of various French short story collections about series of different women – Nerval's Les Filles de feu, for example, or even Barbey d'Aurevilley's Les Diaboliques. Cocteau has a similar tendency to see women as symbols of some ‘eternal feminine’, but, generally preferring men as he did, he doesn't eroticise them in anything like the same way.

The sketches were originally written to accompany illustrations in a book, and they are very short. What makes them worthwhile are Cocteau's turns of phrase, which everywhere show a wonderful range of vocabulary and a good eye for descriptive flourishes. The Duchess of Étampes has the air of ‘a mouse that's been changed into a princess’, ‘toujours prompte à se loger dans les fromages’; Louis XIV is described in passing as ‘a monumental masterpiece of self-satisfaction’; Madame de Pompadour is ‘a fairy, but a fairy that changes footmen into mice and coaches into pumpkins’; Anna de Noailles has ‘the thin shoulder of a Spanish Christ’. On Joan of Arc he begins intriguingly:

Of all the writers of France, Joan of Arc is the one I admire the most. She signed her name with a cross, not knowing how to write. But I speak her language….

It's all very fresh and very clean. A relatively inconsequential work, no doubt – but for me, having pigeonholed Cocteau as purely an avant-garde experimentalist, it was quietly revelatory.

Echo the lobster

I can hear the waves sucking at the land's edge; I can hear the parables, the fables of water, the elusive but lyrical weatherglass vocabularies of water.

The third in Rikki Ducornet's elemental tetralogy, The Fountains of Neptune picks up some threads from the first two books, drops others, and spins some new ones to create a dreamy but sluggish narrative about a boy who spends half a century lost in a coma, falling unconscious in 1910s France and waking up, two world wars later, with his childhood completely lost to him.

‘Water, both real and metaphorical,’ as Ducornet nudges us, ‘is in evidence everywhere.’ It is an accident in the water that sends our narrator Nicolas into his fifty-year sleep; the sea also had something to do with the mysterious loss of his parents; and most of all, the ocean, transparent but also deep and unknowable, functions as a symbol of the unconscious that Nicolas is trapped in for so long.

The most successful parts of the book are the early sections describing Nicolas's childhood in a French fishing village on the Atlantic coast – a chaotic, dangerous world of sailors and down-and-outs that might remind you of the first few chapters of Moby-Dick, or alternatively, depending on your frame of reference, of certain tavern scenes from Pirates of the Caribbean. The seafront bars are presided over by a monstrous ship's carpenter and drunkard called Toujours-Là, whose misogyny and dark, destructive Manichaeanism continues an archetype that began with the Exorcist in Ducornet's first book and was developed by de Bergerac in the second.

‘Don't believe the crap you hear!’ he barked. ‘The universe and all its filthy planets were not created by God but by the Devil. Every morning the sun rises with an empty belly and at night she sinks bloated with blood. You've seen how the moon circles the world like a clean bone?’ I nodded. ‘Like a skull licked clean of meat,’ he insisted.

Like many of her previous characters, Toujours-Là sexualises everything, and turns every little circumstantial phenomenon into a matter of strained gender relations. You know, like this:

He groaned and his lips were flecked with foam. ‘I swear: THE FOG STILL SMELLS OF THAT SLUT'S CUNT!’

The book comes disturbingly alive whenever he's around, which unfortunately, and despite his name, is too rarely. Ducornet's exploration of sexual politics and identities – an exploration that to me seemed strikingly fresh and unusual – is indeed rather abandoned in this novel, to be replaced by ideas of the subconscious. The themes are not unrelated, but I couldn't help feeling a bit disappointed that she'd dropped what I thought of as her specialist subject.

The thing is that Nicolas, the narrator, is just not a very compelling central character. (His nickname, Nini, suggests the French phrase for ‘neither…nor’.) And his narrative voice also falters at times: he says things like, ‘Thinking of him now, my heart pulses like a full-fed river,’ which, without wanting to speak for my entire gender, doesn't seem like a very guy-ish thing to say, somehow. Consequently his psychiatric problems and their solution never really felt very important, even though Ducornet has some interesting things to say about the way our unconscious minds seem to work.

‘We forget that thought is a process which has evolved over the ages from anterior stages. Just as our finger-bones still resemble those of the lizard, so at depths deeper than dreaming our thoughts may echo the lobster's.’

There is something unintentionally funny about the use of the word ‘lobster’ there which, again, makes me worry that she is not totally sure-footed in the way she puts this story together. On the other hand, every now and then you will still come across a sentence that demands to be enjoyed more than once.

The smell of smoke which still permeates the spa – stronger, even, than the stench of sulphur – is not the odour of war but of skin kindled and rekindled by unconsummated desire.

It is instructive – though a little frustrating – that this book covers such a dramatic period in European history without really touching on any of it except in passing: Nicolas sleeps through it all. A case is being made here (on my reading of the book anyway) for the primacy of the interior world over exterior events, even ones this earth-shattering: there is an argument in here that what we invent – let us go ahead and use the word ‘fiction’ – is just as real as the real world, indeed in some ways is more real.

I insist that the self is rooted in nostalgia and reverie, and that they are the fountains of Art. I argue that Art reveals the real. That the existential is always subjective. All that is true is hidden deep in the body of the world and cannot be taken by force. It must be dreamed and attended and received with awe and affection.

I am not sure how far I would accept this argument (there is a very valid counterargument involving the word ‘self-indulgence’), but I liked seeing it made in this interesting way. Overall I found this book less successful than its predecessors, but there's still a lot of interesting ideas to get to grips with – and other concerns aside, it's always a pleasure to swim for a few days in Ducornet's salty, pelagian prose.

The Trial

USHER: Goodreads court is now in session, the Honourable Judge Chandler presiding. All rise.

JUDGE: Mr Wise, you appear before the court today on the charge of failing to adore Infinite Jest, an act in gross and flagrant violation of basic Goodreads standards of decency. How do you plead?

WARWICK: Well...I mean presumably this kind of thing is all subjective opinion, so—

PROSECUTOR: Let the record show that the defendant utterly fails to deny his foul sin.

WARWICK: Hang on—

JUDGE: So noted. If found guilty, the maximum sentence I can hand down is...DEATH.

GOODREADS MEMBERS (from gallery): Hooray! Kill him! Burn the heretic!

WARWICK: Whoa, wait a minute there, don’t you have to assign me some kind of lawyer or something, so I can defend myself? Like in Perry Mason?

PROSECUTOR: Your honour, in view of the gravity of his crimes, we believe the defendant should be compelled to represent himself.

JUDGE: I agree. Do you have any evidence to present in your defence, worm?

WARWICK: I’m glad you asked, m’lud, and thank you for showing such admirable neutrality.

VOICES FROM CROWD: Get on with it, scum!

WARWICK: All right! Well, to be completely honest, my heart began to sink from the very first page. This was my first exposure to Wallace’s fiction, so I was paying quite close attention to the opening paragraphs to try and soak up this style that so many people have fallen in love with. Defence Exhibit A – the opening:

I am seated in an office, surrounded by heads and bodies. My posture is consciously congruent to the shape of my hard chair [...]. My fingers are mated into a mirrored series of what manifests, to me, as the letter X.

WARWICK. I submit I was justified in feeling immediate concern that the prose is awkward, unlovely, and try-hard, with outbreaks of horrendous juvenile alliteration.

PROSECUTOR: Objection! The opening section is clearly narrated by a precocious child genius, making the tone entirely appropriate.

JUDGE: Sustained.

WARWICK: That’s true. And I was definitely willing to go along with that. The problem is that as the book goes on, you start to realise that basically all his narrators sound pretty much the same – they’re all variants on the same depressive, overeducated outsider, speaking in these jagged, straining, uncomfortable sentences. On the few occasions when he attempts social dialects beyond his own – including a few passages of extremely ill-advised colloquial Ebonics – it sounds more like a grotesque parody than any serious attempt at a socially inclusive writing style. Besides, is it really an excuse for a writer to say ‘My characters all happen to talk like malfunctioning robots, so you’re just going to have to put up with it’?

PROSECUTOR: ‘Overeducated’? Really? That may apply to the Incandenza family, but it’s hardly something you could accuse the residents of Ennet House Drug and Alcohol Recovery Center of. Isn’t it, in fact, the case that Wallace’s daring new amalgam of contemporary patois and technical jargon simply went over your head?

WARWICK: Objection. Beyond the scope.

JUDGE: How is that beyond the scope?

WARWICK: I don’t know, it’s just one of those things they always say on The Good Wife.

JUDGE: Overruled. Answer the question.

WARWICK: All right, I don’t think it’s going over my head, no. The writing style is certainly innovative, but mainly in the sense that he sounds stilted and infelicitous in ways that no one has come up with before. His pile-ups of noun-phrases are particularly awkward, the nouns’ plurals’ genitives’ apostrophes so aggressively correct that they actually manage to look wrong. I hate the sloppy attempt in general to use exaggerated colloquialisms as a deliberate style – this habit he has of rambling vaguely around a topic for several paragraphs in the hope that one of his phrases will hit home. I like writers who craft and refine their thoughts before typing them out, not during. Overall I just felt there was a horrible uncertainty of tone, the narrative voice channel-hopping compulsively from slangy to highly mannered to jargonistic, often within the same sentence. It doesn’t cohere, but more to the point it doesn’t feel like DFW is in any control.

PROSECUTOR: Does it not occur to you that this might be done for deliberate effect? Or were you perhaps just put off by all the long words? (laughter from the jury)

WARWICK: Well...I’m reasonably sure it’s not that. I love complicated books with gigantic, exuberant vocabularies. It’s just that here, because of the general sense of bloated free-fall, it all just seems so purposeless, so gratuitous. To me he comes across less as an artist with a fat vocabulary than a hack with a fat thesaurus.

(Woman in gallery faints)

MAN IN GALLERY: You monster!

WARWICK: Defence Exhibit B, m’lud – a description of a character’s smile, which is said to be ‘empty of all affect’:

as if someone had contracted her circumorals with a thigmotactic electrode.

PROSECUTOR: Of course, one of those smiles. I can picture it perfectly.

WARWICK: You bloody can’t! It’s complete bollocks! ‘Circumoral’ isn’t even a noun, is it? And a lot of the time this kind of thing is stretched into full paragraphs – have a look at this single sentence, Exhibit C, which is in no way unrepresentative:

And as InterLace’s eventual outright purchase of the Networks’ production talent and facilities, of two major home-computer conglomerates, of the cutting-edge Foxx 2100 CD-ROM licenses of Aapps Inc., of RCA’s D.S.S. orbiters and hardware-patents, and of the digital-compatible patents to the still-needing-to-come-down-in-price-a-little technology of HDTV’s visually enhanced color monitor with microprocessed circuitry and 2(√area)! more lines of optical resolution – as these acquisitions allowed Noreen Lace-Forché’s cartridge-dissemination network to achieve vertical integration and economies of scale, viewers’ pulse-reception- and cartridge-fees went down markedly; and then the further increased revenues from consequent increases in order- and rental-volume were plowed presciently back into more fiber-optic-InterGrid-cable-laying, into outright purchase of three of the five Baby Bells InterNet’d started with, into extremely attractive rebate-offers on special new InterLace-designed R.I.S.C.-grade High-Def-screen PCs with mimetic-resolution cartridge-view motherboards (recognizably renamed by Veals’s boys in Recognition ‘Teleputers’ or ‘TPs’), into fiber-only modems, and, of course, into exrtemely high-quality entertainments that viewers would freely desire to choose even more.

WARWICK: This passage also contains three endnotes, which I will not go into for the sake of all our sanity. And don’t even get me started on Wallace’s Latin, which he persistently misunderstands. One footnote reads ‘Q.v. note 304 sub’, which is borderline illiterate – ‘q.v.’ is used after the thing you want to reference, and ‘sub’ is a preposition, not an adverb. What he apparently means is ‘Cf. note 304 infra.’ I couldn’t normally care less about this sort of thing, except that in this book it coexists with a laboured subplot about militant ‘prescriptive grammarians’, for whom DFW clearly has much misguided sympathy.

PROSECUTOR: Your honour, surely it’s now clear that the defendant is trying to build a case based on trivial inconsequentialities of personal style.

WARWICK: I know it seems like nit-picking, but the thing is these little mis-steps here and there all contribute to a general sense that you are not in safe hands. It’s like his proliferation of initialisms – why are E.T.A. and A.F.R. and U.S.A. written with dots but MDMA and WETA and AA without them? There’s no answer except general inconsistency, which fans will no doubt tell me is intentional but which is no less annoying for that. The same goes for Wallace’s pseudo-encyclopaedic knowledge base. Hal Incandenza is supposed to be an etymology expert who grew up memorising the OED. But every time we see this put into practice, it’s hopelessly wrong. E.g.: “There are, by the O.E.D. VI’s count, nineteen nonarchaic synonyms for unresponsive” – which makes no sense, because OED 3 won’t be completed for another 25 years or so so there’s no chance of getting to “VI” by the near-future of the novel’s setting; and anyway the OED doesn’t even list synonyms because it’s a dictionary, not a thesaurus. He traces the word anonymous back to Greek but the Greek is horribly misspelled; he traces acceptance back to “14th-century langue-d’oc French” but this phrase is both oxymoronic and flat-out wrong. Where is the research here? All through the book there is a profound feeling that David Foster Wallace did not really understand the things he was looking up in order to seem clever.

PROSECUTOR: Need we remind you that this is a work of fiction and not an academic thesis?

WARWICK: Again, it’s about confidence in your author. Mine quickly evaporated. I’m concentrating on language stuff only because it’s an area where I have an admittedly very dilettantish but somewhat active interest. People who know more about these things than me tell me his maths is equally dodgy. Now contrast all this with a writer like Nabokov or Pynchon, to whom Wallace is sometimes cavalierly compared. When I read Pynchon I can spend hours chasing up throwaway references to some obscure language, some astronomical phenomenon, a paragraph of Argentine politics or an obsolete scientific theory – it’s part of the fun of these big encyclopedic books that you can research all the related knowledge that lies just outside the margins. The references hold up and they enrich the reading experience. When I try and do the same thing with DFW, I always seem to come away with the conviction that he doesn’t really know what he’s talking about.

PROSECUTOR (with heavy sarcasm): How unfortunate that so many people overlooked this and mistakenly found his writing moving and powerful.

WARWICK: Oh come on, don’t be like that. I am delighted that some people love his style, it’s just not for me. I totally admit that this is personal preference. I, personally, like writers who craft beautiful sentences. In my opinion, Wallace is just not very good at the level of the sentence, or even of the paragraph. But he can be great over longer distances – at the level of the chapter or long passage. There are several extended sequences of Infinite Jest that have a kind of cumulative power and excitement to them that I admired very much indeed. They were just padded out with far too many passages of inexcusable tedium.

VOICES FROM CROWD: Boo! Hanging’s too good for him!

JUDGE (banging gavel): Order! Order! (to the prosecution) Cross-examination?

PROSECUTOR: Extremely cross, your honour!

JUDGE: No, I mean do you want to cross-examine the witness.

PROSECUTOR: Oh. Yes! Or rather – (consulting papers) prosecution chooses to call a new witness, your honour – the defendant’s wife.

WARWICK: What?! You can’t—

Enter HANNAH, looking emotional.

PROSECUTOR: You are the defendant’s wife, are you not?

HANNAH (biting lip): I am.

PROSECUTOR: And isn’t it the case, ma’am, that on more than one occasion over the past few weeks, you witnessed the defendant audibly chuckling over what he was reading?

HANNAH: I...I might have done.

PROSECUTOR: Moreover on several occasions did you not see him underlining passages he thought particularly admirable?

HANNAH (fighting back emotion): I...yes. Yes, I did.

PROSECUTOR: And is it not true that those passages included, but were not limited to, the description of Poor Tony Krause having a seizure; the fight outside Ennet House; and Don Gately’s fever-dream sequences?

HANNAH (bursting into tears): It’s true! He said one of them was the...the best thing he’d read all year. He recited bits of it out to me in bed and everything.

PROSECUTOR: And can you see the man who said these things anywhere in this courtroom?

HANNAH (pointing at defendant): There! That’s him! That’s the man! Gaargh!

PROSECUTOR: No further questions, your honour.

HANNAH is led out in tears.

WARWICK: I – what?! This is ridiculous! Objection!

JUDGE: What is the nature of your objection?

WARWICK: The nature of it? Um...what’s that one about badgers, again?

Pause.

JUDGE: …Badgering the witness?

WARWICK: That’s it! He was badgering her! She just got totally badgered!

JUDGE: Overruled.

WARWICK: Look, this is an eleven-hundred-page book. If a monkey throws a thousand darts at a dartboard, he’s going to score a couple of bullseyes. He’s also probably going to hit you in the eye a few times. And in the context of this metaphor, a monkey-inflicted dart-wound to the face can be taken as the equivalent of, say, an unforgivably tedious description of a geopolitical tennis game.

PROSECUTOR: The point remains, however, that you found yourself moved by parts of this book, didn’t you? Affected by the characters’ story?

WARWICK: Sure. Some characters worked better than others. I thought Don Gately in particular was a wonderful creation and I only wish he’d been in a tighter and better-controlled novel.

PROSECUTOR: You were moved, gripped, excited – even aroused at times.

WARWICK: Well, I wouldn’t go that far.

PROSECUTOR: Oh really? Isn’t it the case that, on one occasion last week, you found your mind, in an idle moment of alone time, returning to a certain cheerleader-based episode of mass knickerlessness...?

WARWICK (leaping out of seat): Ob-jection, your honour!! Surely this line of questioning can’t be appropriate!

JUDGE: Oh...go on then, sustained. I really don’t want to hear about it.

Sighs of relief from public gallery.

WARWICK: Although, thinking about it, the query does serve to highlight a certain strain of misogyny that bothered me about the book – where the narrator gives Avril Incandenza extra value by repeatedly telling us that she is particularly gorgeous ‘for a woman her age’, while the nearest thing we have to a female lead is known as ‘PGOAT’ – sorry, ‘P.G.O.A.T.’ – the ‘Prettiest Girl Of All Time’ – and is also defined by her physical attractiveness, or the possible marring thereof.

PROSECUTOR (rolling his eyes at jury): Oh that’s right, play the sexism card now. And I suppose you were equally unmoved by the gripping descriptions of social deprivation – an insight into a world that doubtless a middle-class bourgeois reader like you couldn’t hope to evaluate?

WARWICK: First of all, you should probably be careful what you assume about my background. Second of all, yes some of it worked really well. But again, there is a lack of authorial control. A lot of the violence and stories of drugged-out atrocities start off being genuinely disturbing, but end up going so far that they take on a Grand-Guignol aspect and become too ludicrous to take seriously. When one woman at an addiction meeting mentions her father’s late-night visits to the bedroom of her severely disabled sister, it’s very creepy and upsetting. But Wallace can’t stop himself going on to give us three full, unnecessary pages of detailed “incestuous diddling” (his phrase) which turns the whole thing from disturbing into cartoonish and silly.

PROSECUTOR: So there’s something ‘silly’ about sexual abuse, is there?

WARWICK: I’ll ignore that. Look, I agree that there were parts of this book that I enjoyed very much, of course there were. But I would draw your attention to the fact that during these moments of narrative brilliance, the footnotes and speech tics and other po-mo devices suddenly dry up: he doesn’t need them. This leads me to conclude that they really serve no purpose except to distract from the turgid flabbiness of other sections of the novel. Whose plot, by the way, goes absolutely nowhere – nothing is resolved and no questions are answered.

PROSECUTOR: Again, we would argue that this is deliberate, your honour – forcing the reader back to the text so that the book itself becomes an ‘infinite’ form of Entertainment like the one it describes.

WARWICK: Oh come on. This argument stretches ‘generosity to the author’ beyond the bounds of credibility.

PROSECUTOR: And yet somehow, reviewers who are actually paid to review books – unlike you – have described this novel as ‘profound’ and ‘a masterpiece’ and ‘brilliant and witty’ – refer to prosecution exhibits A through W.

WARWICK: Let’s not forget the London Review of Books review, Defence Exhibit D – and I quote:

[I]t is, in a word, terrible.... I would, in fact, go so far as to say that Infinite Jest is one of the very few novels for which the phrase ‘not worth the paper it’s written on’ has real meaning in at least an ecological sense.

(Shouts of anger from public gallery.)

JUDGE: You disgust me. Are we ready for sentencing?

WARWICK: Wait! Wait! I have one more witness to call!

JUDGE: Very well. Who?

WARWICK: I call... (dramatic pause) … David Foster Wallace!

Pause.

PROSECUTOR: I hate to break it to you, but....

WARWICK: Look, if you can drag my wife on to the stand, then I can sure as hell get a dead author to appear.

JUDGE: Oh for goodness sake...fine. Call David Foster Wallace!

Enter DAVID FOSTER WALLACE in regal bandana. The crowd genuflect.

PROSECUTOR: You are David Foster Wallace, are you not?

WALLACE: And so but then but so yes, I am.

PROSECUTOR: Would you describe the accused as an intelligent reader?

WALLACE: No, I would describe the accused as a dick.

PROSECUTOR (to defendant): Your witness.

WARWICK: Right. Er…Mr Wallace, is it true that when asked to name your favourite writers in literary history, you reeled off a list that included ‘Keats’s shorter stuff’ and ‘about 25 percent of the time Pynchon’.

WALLACE: I think you know that’s true.

WARWICK: OK, so leaving aside the fact that this is pretty fucking rich for someone who’s attempted a wholesale rip-off of Pynchon’s approach – doesn’t this tone, this attempt to sound discriminating, go to the heart of my problems with Infinite Jest?

WALLACE: You tell me, brother.

WARWICK: I mean, am I wrong in connecting this quote to your problems with dodgy research and sloppy editing? Isn’t it all the sign of some kind of larger underlying problem – a writer who is basically feeling insecure and out of his depth, and who tries to cover all this up by overwriting – by trying to appear much more intelligent and well-read and knowledgeable than you really are, and in the end didn’t it all just get too much for you to control? Or are my thoughts just being coloured by what I know happened to you twelve years after you published it?

DAVID FOSTER WALLACE rubs his beard.

WALLACE: Maybe you’re right. Maybe there is some insecurity behind it. Maybe I was too ambitious for my own good. Is that, like, a crime? You know, some guy once said that all novels are just volumes of a writer’s autobiography. This is mine. And you know what, maybe somewhere inside, I hoped that this insecurity, this loneliness, this crippling psychic fucking pain that you’ve so brilliantly picked up on, would actually speak to somebody. Would actually touch somebody, make them feel like they weren’t alone. Someone who was reading it and who thought they were the only one. That it might make them feel better, just for a moment. Isn’t that what this book’s really about? Isn’t that what all literature is really about?

Silence in court.

WARWICK: …Well fuck. I just feel bad now. You know what, David Foster Wallace? You’re right. You really are. I do admire your ambition, and I wish I liked your book more. Too many people I like and respect have loved this book for me to dismiss it. What happened to you is absolutely awful and I wish you’d stayed around long enough to have another go.

DAVID FOSTER WALLACE bows and throws his bandana into the public gallery. GIRL in crowd spontaneously orgasms. MAN in crowd throws off his crutches and walks.

WARWICK: The truth is, I can see why some people like this book very much. I just find it hard to understand why so many people my age think it’s the novel of our generation. Infinite Jest to me reads like a fascinating first draft. I feel about it something that a lot of people often say in reviews but that I’ve never really felt about a big book before: that it desperately needs editing. And although a lot of people talk about how good the writing is, there are very few examples of what they mean – I find a worrying lack of close reading in the most enthusiastic reviews, but again this could be personal preference because I happen to like reviews that pin their opinions to the text. If nothing else, your honour, I hope I have given enough examples to show that my aversion to this book is not down to contrariness or disrespect, but just insurmountable problems in my reaction to the writing.

JUDGE: No, you haven’t. In view of the wanton, reckless nature of the crimes committed, I have absolutely no hesitation in finding you guilty. You’re guilty, guilty! Guilty as a man can be. (donning a black cap) You are hereby sentenced to be clubbed to death by a hardback copy of Infinite Jest. And may God have mercy on your soul.

The PROSECUTOR starts handing out pitchforks to the crowd.

WARWICK: I wish to appeal the sentence, m’lud!

JUDGE: There is no higher authority than Goodreads.

WARWICK: On the contrary, Judge Chandler! I wish to appeal...(dramatic pause)...to Amazon!

CROWD: Gasp!

Enter AMAZON REPRESENTATIVE in suit. His pockets bulge with money and banknotes protrude from his sleeves and trouser-cuffs.

AMAZON REP: We at the Amazon corporation – er, I mean the Amazon family – hereby grant the defendant’s appeal. If he were killed, we would no longer be able to profit from his compulsive Amazon buying habits.

PROSECUTOR: You mean—not only does he not like Infinite Jest, but he also shops at Amazon!?

MAN IN CROWD: He killed my local bookstore!

WOMAN IN CROWD: He’s literally Hitler!

ALL: Get him!

WARWICK: Uh-oh. Time to scarper! (Exit, pursued by cast. And a bear.)

Curtain.

EPILOGUE

(from ‘James O. Incandenza: A Filmography’)

The ONANtiad. Year of the Whopper. Latrodectus Mactans Productions/Claymation action sequences © Infernatron Animation Concepts, Canada. Cosgrove Watt, P. A. Heaven, Pam Heath, Ken N. Johnson, Ibn-Said Chawaf, Squrye Frydell, Marla-Dean Chumm, Herbert G. Birch, Everard Meynell; 35 mm.; 76 minutes; black and white/color; sound/silent. Oblique, obsessive, and not very funny […].

Winning on points

The Goodreads Censorship Fiasco of 2013 has got a lot of people considering works by Adolph Hitler, convicted sex offenders, and flagrant P2P artists. I have found myself repeatedly thinking of a particular routine from 90s stand-up comedian Stewart Lee.

If you don't know Lee, his style is not easy to demonstrate through quotation. His material relies on carefully-layered silences and repetitions, tiny nuances of expression, and sequences that derive their humour from the cumulative probing of audience expectations. In other words, there are no one-liners or identifiable ‘jokes’, and consequently a lot of people find him irritating and tedious. I love him. I urge you to listen to a couple examples of his style, such as this routine about Braveheart daringly performed in Glasgow, or maybe this one on Osama bin Laden.

Having made a huge contribution to the British alternative comedy boom in the early 90s, Stew kind of dropped off the radar a bit, until in 2005 he suddenly hit the headlines again in a massive way. He had co-written a brilliant piece with composer Richard Thomas called Jerry Springer: The Opera, which had just finished a West End run and been filmed for broadcast on the BBC. A right-wing Christian pressure group called Christian Voice decided to use the planned broadcast to drum up some public attention, based on the fact that the show involved a lot of swearing and featured a sequence in which Jesus appears in a nappy.

Elaborate protests were staged, 55,500 people complained, BBC executives were advised to go into hiding, and theatres everywhere cancelled their plans to stage the show on tour. Stewart and Richard Thomas lost a lot of money. The whole thing briefly became something of a public scandal, and plans were made to prosecute Stew and Richard under old-but-still-on-the-books blasphemy laws.

It was at this point that Stew went on tour again with a show ironically named '90s Comedian. He was not in a happy place. But his response to being pursued for blasphemy and having his work pulled from theatres around the country was rather heartwarming, even if it shocked a lot of people who saw the show: he built a long and scatologically detailed routine around a drunken, nauseous encounter with Jesus Christ. In the spirit of the Goodreads regulations I will quote from the relevant transcript, taken from a Cardiff gig in 2006:

But then I felt the sick rising in me again, and I thought, ‘What am I supposed to do now?’ […] And then I opened my eyes and I looked down, and He was there again, Jesus, on my right. But this time He had His back to me and He was doing a kind of handstand by the sink. And his raiment had slipped down, it looked like a kind of third-length, floral print hospital gown. And He had His right hand on the floor to, to balance Him upside-down, and with His left hand He was using the fingers to kind of splay open His anus. As if what He…As if what He wanted was for me to vomit into the gaping anus of Christ.

[off-mic, shouting] And don't imagine, Cardiff, that I come here and talk about this lightly, OK? I thought about it, I asked around – well, I know it's a bit much but I asked around, I said to – oh look, I asked Tony Law, he's a Canadian stand-up comic, he's the most reasonable man I know, I said to him, ‘Tony, do you honestly think I can go round the country in front of people and use the phrase, “I vomited into the gaping anus of Christ”?’ And he said, ‘Well, possibly, if it's in context. But,’ he said, ‘you won't be able to use it as the title of a live DVD.’ I said, ‘I'm not going to do that, Tony, I'm not insane.’

But imagine this situation, it is impossible. There is no right way out of it. I bent down, I said to Jesus, ‘Are you sure this is what you want?’ And He said to me, ‘Look, you're going to be taken to court for blasphemy for doing nothing, I feel like I owe you one, knock yourself out.’ So against my better judgement, 'cause He told me to, I did it. I vomited into the gaping anus of Christ till the gaping anus of Christ was overflowing with my sick. I did that. Are you happy now?

Quoting this out of context is rather unfair, especially since this section is followed by a beautiful and funny exploration of why offending people in this way is sometimes absolutely necessary. Although, as I said, quite a few reviewers were shocked by '90s Comedian and didn't really understand it, the show was in general hailed as a small masterpiece and it relaunched Stew's career.

This book, which is built around transcripts of this and his other two big shows of the 2000s, transcends its genre by virtue of the enormously thoughtful footnotes and introductions and appendices discussing how the bits were written and performed and the thought processes behind them. On the genesis of the vomit/Christ sequence, Lee says a lot of interesting things about how he wanted to react to the attempted censorship of his material:

Was it possible to write something which, when reduced to its content alone, would be impossibly offensive, featuring as it did a urine-and-vomit-fuelled encounter between a drunk comedian and a holy figure in a cramped toilet, and yet to write and perform it in such a way that it became tender, moving and meaningful over and above the supposed taboo nature of its content alone? […] In short, if you felt our careful, theologically rigorous and kind-hearted opera was blasphemous, well, try this on for size, you twats, and – you know what? – I will still win on points. I will make meaningful religious art out of toilet filth, just to beat you.

This combination of, on the one hand, a big fuck-you, and on the other a thoughtful argument about rights and responsibilities, is something I see a lot of reviewers going for here as well (and often pulling it off brilliantly). It's an approach I like very much, and if it gives me an excuse to mention this magnificent book – a key text in the field – then so much the better.

A man walks into a bar…

It's nice to see that I can still get excited about narrative tricksiness from time to time. This was wonderful. Who would have thought such an elliptical prose style could conceal such comic potential? Funny, clever and moving...Coover has been on my radar since I started reading Rikki Ducornet (who seems to be his biggest fan) but this makes me determined to track him down properly.

Clear fifteen minutes in your day, pour yourself a beer, and read it here, unless you've already done so, it's hard to tell.

Brazilians in the Belle Epoque

Hands-down the most entertaining book I've read all year. You need this in your life if you have any interest at all in French literature, the life of the mind, the creative process, or Gallic bitching on a monumental scale. Especially the last one.

Every page, and I mean every page, of this book contains one or more of the following:

1. A perfectly-polished aphorism;

2. An astonishing anecdote about a famous writer, or painter, or member of royalty;

3. A worm's-eye view of some major historical event;

4. A jaw-dropping insight into the ubiquity of nineteenth-century misogyny

…or all four. The nature of the Goncourts' social circle means that even the most Twitter-like entry of daily banality becomes interesting (‘A ring at the door. It was Flaubert’), but more to the point there is so much here of the real life that never found its way into the fiction of the time. Reading this feels like finally finding out what all those characters in nineteenth-century novels, with their contrived misunderstandings and drawing-room spats, were really thinking about – the salacious concerns that lie behind all the printable novelistic metaphors. When the Goncourts and their famous friends get together for a chat, instead of just talking about who batted their eyelashes at whom last night, they are more likely to wax lyrical about

the strange and unique beauty of the face of any woman – even the commonest whore – who reaches her climax: the indefinable look which comes into her eyes, the delicate character which her features take on, the angelic, almost sacred expression which one sees on the faces of the dying and which suddenly appears on hers at the moment of the little death.

la singulière et originale beauté du visage de toute femme qui jouit—même chez la dernière gadoue—, de ce je ne sais quoi qui vient à ses yeux, de cet affiné que prennent les lignes de sa figure, de l'angélique qui y monte, du caractère presque sacré que revêt le visage des mourants qui s'y voit soudain sous l'apparence de la « petite mort ».

(An idea expressed in almost identical terms, incidentally, more than 150 years later in Nicholson Baker's The Fermata.) Or about their aversion to the ‘oriental practice’ of women shaving their pubic hair:

‘It must look like a priest's chin,’ said Saint-Victor.

It is all amazing stuff. The Goncourts are alert to the best gossip, the most entertaining and revealing anecdotes; their keen sense that they are underappreciated geniuses drives a lot of their observations of the people around them who are (as they see it) getting the success that they, the Goncourts, deserve. This is lucky for us, because it keeps them deeply interested in the artists around them to the very end.

The most prominent of these is Zola, who first pops up in the journals as an unknown fan. His prodigious work ethic and knack for publicity soon means that he is getting all the glory, and all the money, of being the leader of the new ‘Naturalist’ movement. The Goncourts reckon, not without some reason, that he lifted most of his best ideas from them, and they duly note down all the examples they can find. But they're impressed despite themselves at how good he is with the press; as Zola cheerfully confesses,

‘I have a certain taste for charlatanism…I consider the word Naturalism as ridiculous as you do, but I shall go on repeating it over and over again, because you have to give new things new names for the public to think that they are new...’

The attitude of all concerned towards women is shocking, especially in the early years (Edmond does mature quite a lot towards the end, benefitting from a close and gossipy friendship with Princess Mathilde Bonaparte that was clearly very important to him). The women that get discussed tend to be gaupes ‘trollops’, gueuses ‘sluts’ or gadoues ‘whores’; sometimes translator Robert Baldick even renders filles ‘girls’ as ‘tarts’, which, given the tone, is not unreasonable. The brothers confess somewhere that neither of them has really been in love for more than a few days at a time, and their deepest emotion is always reserved for each other. Edmond's description of his brother's eventual death from syphilis is heart-breaking: ‘This morning he was unable to remember a single title among the books he has written.’

And death does loom pretty large over parts of the journal, which covers such upheavals as the Franco-Prussian War, the Siege of Paris, and the suppression of the Commune – but the Goncourts' eye is always on individual responses, picturesque incident, personal idiosyncrasies.

Neither of them ever marries, although Edmond thinks about it a few times after his brother has gone. He tries to let down gently the few women that approach him. Eventually, in a passage that's somehow both creepy and moving, he confides that he's never really got over his first erotic experience as a young boy, when he was staying in his cousin's house:

One morning […] I went into their bedroom without knocking. And I went in just as my cousin, her head thrown back, her knees up, her legs apart and her bottom raised on a pillow, was on the point of being impaled [enfourchée] by her husband. There was a swift movement of the two bodies, in which my cousin's pink bottom disappeared so quickly beneath the sheets that I might have thought it had been a hallucination…. But the vision remained with me. And until I met Mme Charles, that pink bottom on a pillow with a scalloped border was the sweet, exciting image that appeared to me every night, before I went to sleep, beneath my closed eyelids.

The Journal amounts to an argument that what matters in life is sex, death and literature – only the characters illustrating this are not fictional creations but rather Victor Hugo, Flaubert, Zola, Degas, Barbey d'Aurevilley, Huysmans, Dumas, Oscar Wilde, Swinburne, and Turgenev. It's not only glorious and life-affirming, it's also very moving because even while Edmond rages against how his literary works have been overlooked, the reader is increasingly aware that this journal is going to be everything that they hoped for their novels, and more.

A book is never a masterpiece: it becomes one. Genius is the talent of a dead man.

A talent they obviously had. I would rather read half a page of the Goncourts on Zola than a hundred pages of Zola himself. Indeed right now I feel I'd rather read half a page of the Goncourts on anything than almost anything else.

2

2

7

7

Switzerland summarised in five Scrabble-winning items of vocabulary

![[( A Concise History of Switzerland )] [by: Clive H. Church] [Jul-2013] - Clive H. Church](http://booklikes.com/photo/max/200/300/upload/books/27/33/519dc0a3ce713169c22f8397ce6d8d94.jpg)

EIDGENOSSENSCHAFT

Switzerland is an anomaly in a multitude of ways. One of the most immediately striking is that it has no head of state; the country is run collectively by a Federal Council. (Admittedly, the council does have a nominal president, but he or she has no more power than the other councillors, and the position typically rotates among members year-on, year-off.)

This lack of a single political focus is something that goes back to the very start of the country, which began as a loose confederation (Genossenschaft) of independent sovereign areas, bound together by oath (Eid). If this seems unusual now, consider how truly unique they were in the Middle Ages, hammering out an awkward cooperative existence while surrounded by autocratic feudal lords and monarchs. Yet somehow they managed to avoid getting sucked in to any of them.

The various linked members of this confederacy – now crystallised into separate cantons – didn't always get on very well, and often still don't – a situation aided by considerable local autonomy. Even contemporary Swiss politics sometimes puts you in mind of reading about medieval city-states.

RÖSTIGRABEN

This is the delightful name colloquially applied to the boundary between German-speaking and Romance-speaking parts of Switzerland – literally, the ‘rösti ditch’. Reflecting the country's disparate origins and lack of political centrality, there are four (really, five) national languages: German, French, Italian, and the interesting Alpine descendant of Vulgar Latin called Romansch. If you're not confused yet, bear with me: there are really two "German" languages here – the Swiss form of standard German, used in newspapers and printed material, which is like German German with a few Helvetisms thrown in; and also true Swiss German, which is a separate language altogether and mutually unintelligible with standard German. The situation in Germanophone parts of the country is thus not unlike Scotland, where Scottish English in public life alternates with Scots on the streets, except that crucially, Swiss German is not seen as being low-prestige: it just happens not to be used in writing.

WILLENSNATION

So the Swiss have a lot of local political autonomy. They do not share a common language, or ethnic origin. They certainly don't share a common religion (Zwingli and Calvin were from Zürich and Geneva respectively, so the country was hit pretty hard by the Reformation). So what do they have in common, exactly?

This was the question various Swiss thinkers were asking themselves in the early modern period, when ideas of nationhood were a hot topic in Europe. The answer that became popular involved seeing Switzerland as a Willensnation: a nation formed simply by a collective act of political and cultural will. One of the things this means in practice is that Swiss history and legend has become very important as a shared pool of reference – the Swiss are much more involved with their history than the Brits are, for example (although the Americans probably give them a run for their money).

Time to re-read William Tell.

RÉDUIT

In medieval and early-modern Europe, Switzerland seem to be stuck in an unenviable position, wedged right between the major powers: France to the west, the Holy Roman Empire to the north, and the powerful Italian states to the south. This is one reason they soon developed the policy of "armed neutrality" that later became such a major part of the country's identity.

The fact that they survived at all is mainly thanks to their geographical position, backed up against the Alps in a natural fortress. In fact until the advent of artillery, it was literally impossible to stage a military take-over of the area: there was simply no army in Europe that had the man-power or the technological means to do it. Hence there are endless examples of Swiss militia thrown together from a few small villages that defeated entire Imperial armies, over and over again.

Perhaps this has an effect on a country's psyche. In the Second World War, it formed the basis of the country's policy of the Réduit (‘cubby-hole’), whereby in case of invasion everyone would retreat to the mountains, which were duly planted with camouflaged cannons and gunner emplacements. This network of Alpine armaments was not fully dismantled till 2011.

There is a (doubtless apocryphal) story about a senior Nazi officer having a clandestine meeting with a Swiss general in 1939, in an attempt to win Switzerland over to the Nazi cause. The Germans threatened invasion if Switzerland refused. ‘I can have a million men mobilised overnight,’ the Swiss general calmly pointed out.

‘Then we shall send two million!’ said the Nazi officer.

‘Ah,’ said the Swiss general. ‘But we will fire twice.’

SONDERFALL

Switzerland came through the war with their territorial integrity and their neutrality intact, and they were proud of coming out the other side in one piece. Not having suffered the deprivations of the war years in the same way that the combatants had, their economy boomed. Industrial output went into overdrive and GDP shot up like a bridegroom on Viagra. The number of millionaires also rose precipitously.

Perhaps (some people started to say) Switzerland was somehow special…? It had avoided the problems other nation-states were lumbered with; it had found the magic formula. It was a Sonderfall, a special case.

In some ways it was, and still is. But the honeymoon is long over. Their wartime conduct has been aggressively called into question, especially by the US over the ‘Nazi gold’ issue. An influx of foreign workers and a credit crunch has led to a flourishing far-right in Switzerland, built on fears of Überfremdung or ‘over-foreignisation’ – a fear best symbolised by the nauseating ban on minarets a few years ago. And in other ways too, the country has been slow to modernise socially: women in parts of Switzerland were still excluded from voting in local elections until 1990. No, that is not a typo. Nineteen-fucking-ninety.

Switzerland definitely repays further study, given its many peculiarities, and the two authors here (one an expert on the medieval Swiss, the other an expert on the modern state) rattle through the essentials briskly. This book does what it says on the tin, competently but without flair. However, as a one-volume history of the country down to modern times, it doesn't currently have much competition.

1

1

5

5

Mouse dropping in the pepper

Busty young princess Marie-Adélaïde set tongues and codpieces wagging today as she made her first appearance in court looking dressed to kill in a daring figure-hugging gown. The saucy Savoyarde (34-20-34, after corset) was presented to future hubby the Dauphin – but onlookers said her Alpine attributes also had the King giving her the royal once-over. Official courtiers were unavailable for comment, but sources close to Versailles told us: ‘She may only be 11, but that's hardly likely to stop Louis. Frankly, if we didn't keep a steady supply of hos round here, I honestly worry he'd start humping the furniture.’ ‘House of Bourbon?’ said another. ‘House of Whore-bon, more like!’

This book is essentially a Louis-Quatorzian tabloid.

The problem I had with it was that it felt a bit too light to be valuable history, but at the same time not quite salacious enough to be enjoyed as just good gossip. Antonia Fraser's approach is to tell the story of Louis XIV's reign through the women that were close to him – from his mother Anne of Austria, through his wife(s?) and mistresses, down to his beloved granddaughter-in-law Adelaide – but although it does contain quite a few fascinating anecdotes, overall I felt I didn't finish the book much more enlightened than before I started.

It does drive home to you quite how much Louis, for want of a better word, slutted it up at court. The very fact that there was a semi-official position for his maîtresse-en-titre, complete with suite of royal apartments, kind of amazes me – what on earth did the queen think of it? (One of many fundamental questions that this book doesn't really address.) They all lived in each other's pockets, so nothing can have been a secret, yet the fiction had to be maintained. The queen on one occasion actually walked right past the room where Louise La Vallière was going into labour with Louis's love-child. ‘Are you all right?’ the queen asked, seeing this girl clearly in some pain. Louise, panicking, called back, ‘Colic, Madame, an attack of colic’!

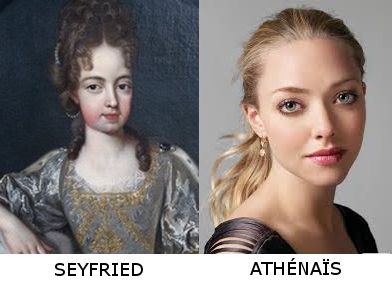

My favourite mistress was Françoise-Athénaïs, a.k.a. Madame de Montespan – the only one who seems to be enjoying herself, she had a famously sparkling line in conversation and also (Fraser seems weirdly shocked by this) liked sex a whole lot. She's described as having long blonde hair, a pouting mouth, and eyes that were ‘huge, blue and very slightly exophthalmic’, all of which makes me think casting directors should be calling up Amanda Seyfried.

Athénaïs happened to be married already; her husband, despite being advised that if your wife's cheating on you with the king you should probably just keep quiet, kicked up a huge fuss about it and ended up getting exiled from court. Back on his estate, he pulled down the gates to his château, telling everyone loudly that his cuckold's horns were now too big to fit through them. Classy way to handle it.

Dominating the latter parts of the book is Françoise d'Aubigné, Madame de Maintenon, who was older than Louis and clearly more of an emotional support for him than a sexual fling. Indeed she didn't really want to be a mistress, as such, preferring the role of religious advisor and loyal friend – but, as Fraser puts it, she ‘decided that a best friend's duty to Louis XIV did unfortunately include sleeping with him, in order to prevent other more frivolous, less religiously focused people doing it without her own pure motives.’ Louis probably married her in secret after his first queen died.

Perhaps my favourite character at court was not a mistress at all, but Louis's sister-in-law – a German princess known as Liselotte. She was rather overweight and hated almost everyone, especially the royal bastards whom she referred to cheerfully as ‘the mouse-droppings in the pepper’. While all around her were consumed with etiquette and courtesy, she was scribbling happily during a particularly nasty cold that she probably looked like ‘a shat-on carrot’, or enjoying impromptu farting competitions with her immediate family (the winner could make ‘a noise like a flute’).

‘I shall look like a shat-on carrot’

Occasionally I questioned Antonia Fraser's methods. She has an admirable desire to make her story readable and compelling, but sometimes she takes liberties to get the job done. Consider this passage:

Louise flung herself trembling on the ground before him. Only then did his glacial reception – she had defied his explicit orders to stay at Versailles – convince her of her terrible mistake. ‘How much inquietude you might have spared me, had you been as tepid in the first days of our acquaintance as you have seemed for some time past! You gave me evidence of a great passion: I was enchanted and I abandoned myself to loving you to distraction.’ The poignant words were those of a young woman in […] the celebrated best-seller of the time, Letters of a Portuguese Nun. They might have been spoken word for word by Louise.

Wha–? You can't do that! You can't just borrow lines from a novel and say, ‘Wow, historical figures might well have said something a bit similar’ – at least not without a lot of care and signposting. This is not cool.

If I look out of my kitchen window, I can see the building where Louis XIV was born – now an overpriced hotel. My daughter plays in the enormous gardens of what was once the royal château of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. So this is a place and period I am particularly interested in, and this book does give you a few clues as to the ‘interesting mixture of sexuality reined in by religious fervour’ that prevailed at the Sun-King's court. But in the final analysis, I find myself craving something a bit more detailed and critical.

tl;dr: Phwoar what a scorcher

The question is whether I will read this based on the author's dubious reputation.

I see that a recent review from Kalliope made the terms-of-use-busting claim that "Manny is [...] Manny!" But are things really that simple? I cannot be the only person who has noticed the striking resemblance between our Goodreads titan and the popular comic-book-artist-cum-practising-magician [a:Alan Moore|3961|Alan Moore|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/authors/1304944713p2/3961.jpg]:

I have it on good authority that the two of them have never been seen in the same room at the same time.

Is there something we should be told?

(Duly shelving as "due-to-author")

2

2

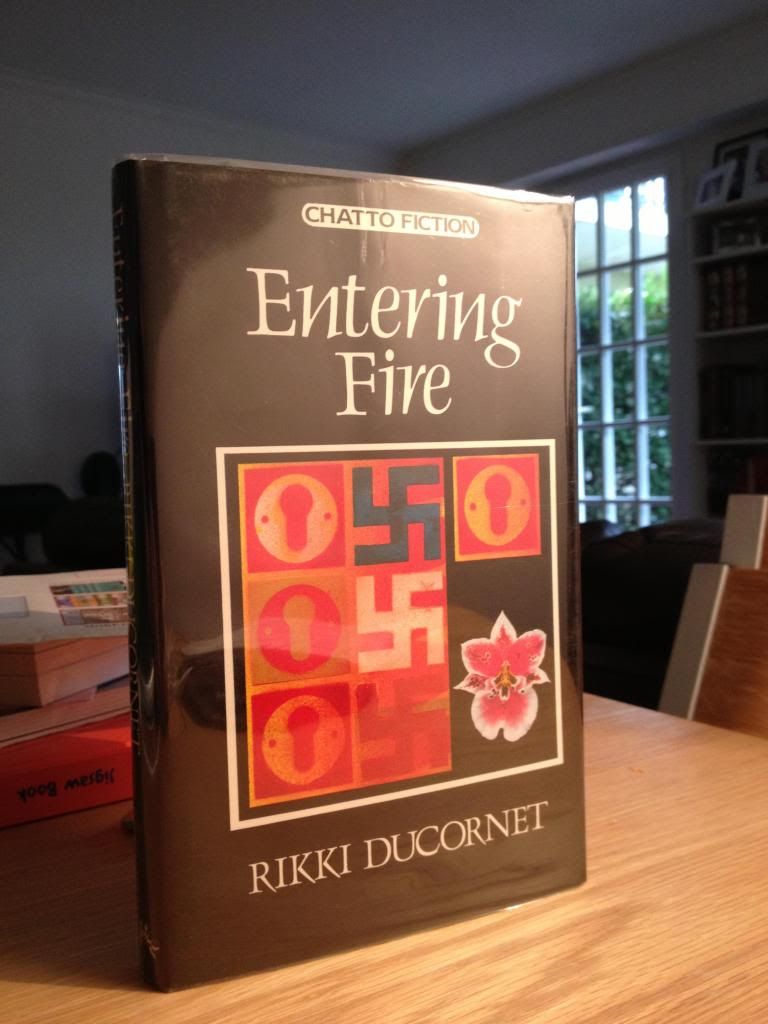

Entering Fire

Water has never been my element. Give me a hot wind. Give me fire.

The second in Rikki Ducornet's loose quartet of elemental novels, Entering Fire is a fantastic blend of high-level botany, extreme racism, tropical fevers and alchemy, all infused with the author's characteristically deep understanding of sexual instincts and behaviour.

Her first book was set in the Loire Valley; this one begins in the same place, but then rapidly expands to take in Occupied Paris, the Brazilian rainforest during the rubber boom, and the paranoia of McCarthyite America. Ducornet is showing off her range, and I liked it very much; there is something almost Pynchonesque in this sexy, dilettantish but deeply thoughtful approach to historical incident.

There are two narrators, father and son: two poles of humanity, two opposed visions of the male experience. The father, Lamprias de Bergerac – a descendant of Cyrano – loves women almost to excess (a trait to which we can note that Ducornet is always very sympathetic). Lamprias is world-renowned as ‘the Einstein of botany’, whose life, when he's not dallying in various exotic brothels, has been dedicated to the study of orchids – those plants known for their ‘impudent display of tiger-striped, peachvelvety, sticky and incandescent genitalia’. Yum!

The son, Septimus, is a nightmarish Céline caricature. A violent antisemite and misogynist, he welcomes the Nazis to France with open arms and contributes gleefully to the ensuing suppressions. Females, with the single exception of his mother, terrify and disgust him: ‘I like to imagine a brothel where the women – and each and every one of them has her feet bound – are infibulated when not in use and tied to their beds. That's my idea of Paradise.’

Septimus's voice is terrifying: he is a continuation of the Exorcist from The Stain, now fully gone over to the dark side. It is instructive, if uncomfortable, to read about the Nazi occupation from the point of view of a character so enthusiastic about it.

His father's narration, by contrast, is lush, verdant, polyphiloprogenitive – full of beautifully pullulating descriptions, such as this sketch of turn-of-the-century Rio:

Etched into my brain are visions of young, green Spanish girls sipping sherbet and preening like grebes on balconies, bouncy French whores nibbling pineapple and dealing out cards, English lasses floating past on imported bicycles and everywhere a European bustle of full skirts. Beneath the tropical sun the women sweated like mares – the odour of their overheated flesh was everywhere – their breasts pressed beneath the lace of their bodices like flowers in a book of verse. And now suddenly I remember the laundresses hanging out the city's wash to dry in the blazing sun. And camisoles and shifts and bloomers and petticoats. There were men in Rio, too, but I took little notice of them….

I mean come on. When Ducornet is in flow like this you feel that you can positively bathe in her prose. She has a tendency of coming out with things that I don't think would ever even occur to me and that I'd be scared to write down if they did: ‘Whores, like orchids, are the female archetype par excellence: painted, scented, seductive,’ she has her most sympathetic character say – but then immediately develops the maxim into something more nuanced:

Beneath their masks, the women of the Palace were fragile, luscious and unique. But the men who visited them were so blinded by lust they never saw what was there, only what was painted there.

Her style, as well as her scope, has developed since the first book: she is slightly more restrained here and more in control. Occasionally this can make her sound a little sententious – that sense of sheer fun has been toned down – but generally speaking, it feels more mature. And I was surprised to see the narrative enlivened by several excellent jokes (not something I'd previously imagined would be her forte):

You will understand why later, when Senator McCarthy asked me if my companion was a Marxist, I answered without hesitation, Yes. Of course, I was thinking of Groucho.

And don't even get me started on the insults – ‘Your mother has a cunt like a hippopotamus yawning’, anyone?

With its two oscillating narrators, the book will whisper to you on a symbolic level too, even if you're not always sure exactly what point is being made. And though Ducornet still sometimes takes herself just a smidgen too seriously for my taste, her sentences are a delight, a wonder, a pure pleasure. Rikki's world is stark and often frightening, but it's also full of sensual delights. I closed the book already craving the chance to spend more time there.

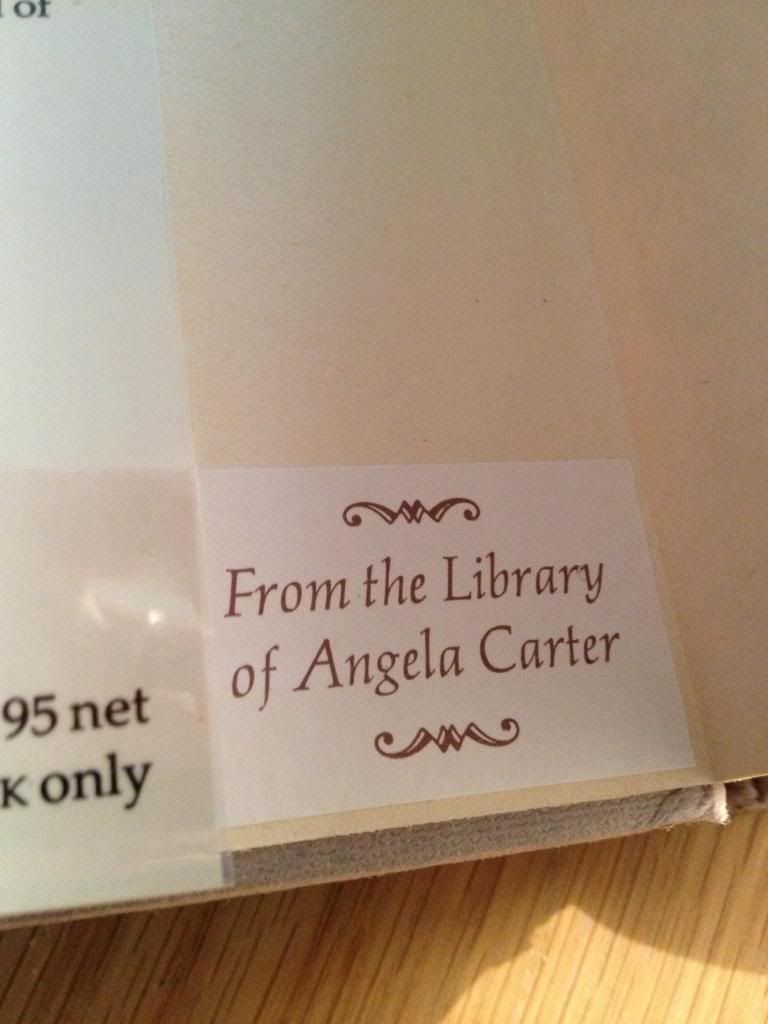

---------------------------------- Original non-review:

Prepare to be jealous. Not only do I have a first edition of Rikki Ducornet's Entering Fire, but I have Angela Carter's old copy.

:-D

Feathery tickles from the little creatures nestling in their underwear

This is the sort of slim, unserious novella that a charitable critic might call a jeu d'esprit and a less charitable one a complete waste of time. The style has been aptly summarised by a previous reviewer as ‘Orientalist porn’, and sure enough the whole thing feels like an extended riff on a Jean-Léon Gérôme painting, perhaps this one:

The Grand Bath at Bursa, 1885

The setting is the closed world of the imperial harem in Ottoman İstanbul. Orkhan, a relative of the sultan, has spent his life locked away in a cage: finally one day he is released, and hailed by the harem girls as their new ruler. But he quickly realises that there is something more sinister going on behind all the sensuous luxury on display, and there's every chance he might not make it out alive.

The approach is episodic and hallucinogenic, with poor Orkhan stumbling tumescently from one steam-room to the next, desperately trying to assert his authority over a series of horny concubines, bored laundry girls and mystic priestesses, who always seem to know a lot more than he does. There is a dwarf, there is crocodile sex, there is a voluptuous fortune-teller who practises ‘phallomancy’ and ‘vulvascopy’. There are Arabian Nights-style anecdotes, such as when the harem develops an infestation of those Persian fairies known as peris: