Warwick

Monað modes lust mæla gehƿylce ferð to feran.

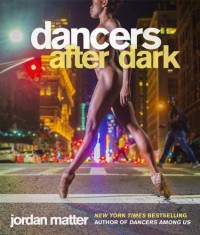

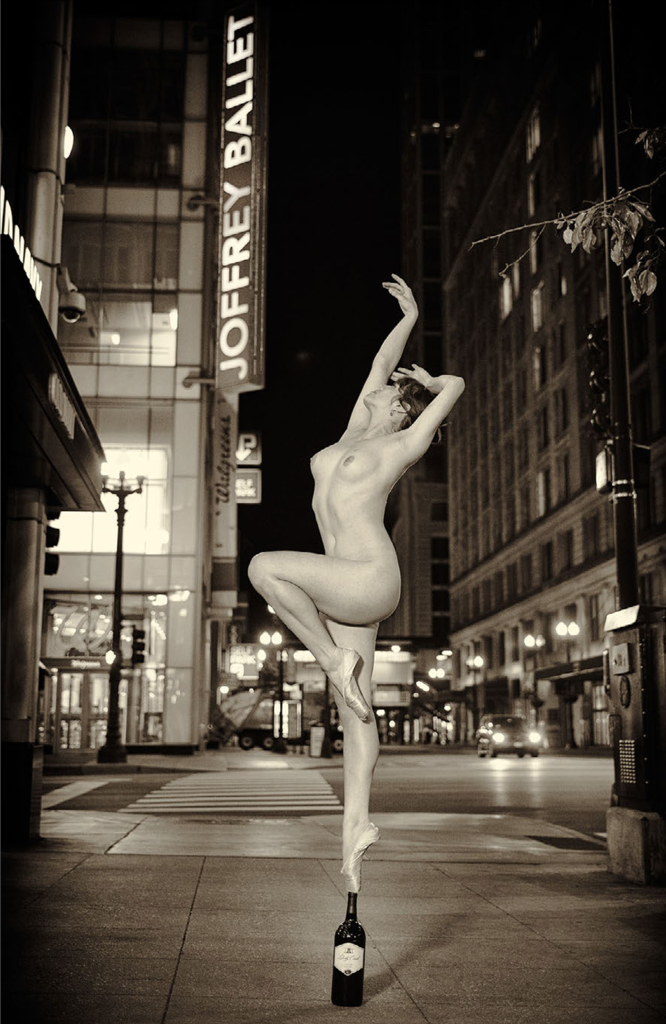

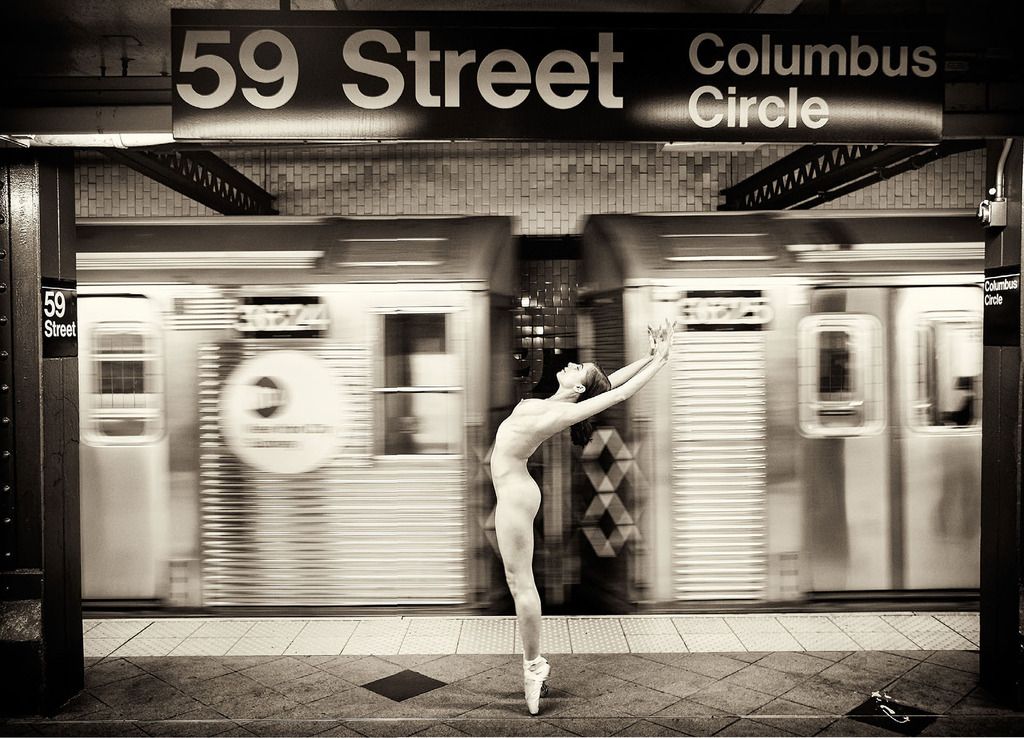

Remarkable photography project from Jordan Matter, who spent two years convincing professional dancers to strip naked and pose in front of city landmarks around the world; it sounds a little prurient, perhaps, but the results are absolutely breathtaking.

The human body emerges in these pictures as a kind of movable sculpture, conveying very little of the sexuality you'd normally associate with nude photography, but calling to mind instead Classical art, anatomy textbooks, and the expression of a complete control over the muscles and gestures of a body in prime fitness. I mean…check this out:

Now that's impressive. A surprising amount of the dancers' personality comes across in their poses, especially considering the amount of bravery it took to capture many of these shots – some of the subjects talk, in a behind-the-scenes section at the end of the book, about the terror and the ‘ecstasy’ of stepping out of their clothes on the middle of Broadway or wherever. I would have liked more of those interviews and stories – Matter says that he had only ten or fifteen seconds to shoot in many cases, not least because of the risk of arrest.

He notes at the beginning that none of the photographs have been ‘digitally altered or composited’, which is pretty impressive – it's hard to believe that the colours at least have not been tweaked in post-production, despite his assurance that ‘Photoshop is unnecessary when dancers are this fearless’. I am frankly open-mouthed in my appreciation of how beautifully he arranged the framing and lighting in these shots, given how little time he had to work with.

It's a strange way to spend two years of your life, but he and his subjects have produced a really wonderful, playful homage to the human body and its relation to our environment. It's not an expensive book, but you should probably factor in the costs of renewing your gym membership, which, after flicking through a couple of pages, will be top of your to-do list.

1

1

The Swiss writer Robert Walser, who has become something of a rediscovered literary darling in recent years, notoriously avoided writing anything in Swiss German, considering this to be eine unziemliche Anbiederung an die Masse, an unseemly pandering to the masses. This brief play, not performed or published in his lifetime, is the one exception. It was written in 1902, when Walser was in his early twenties, staying in a little village on Lake Biel near his sister, and not published until 1972 as part of his Gesamtwerk.

It therefore has its linguistic interest, but as a play it's a bit cringeworthy and – Walser's feelings about dialect notwithstanding – you can see why he never tried to do anything with it. In some ways it's exactly the kind of plot you'd expect a young, artistically-inclined loner to write: a young boy who feels no affection for his family and thinks they don't appreciate him pretends to drown himself in order to make everyone realise how great he was after all.

Annoyingly, instead of slapping some sense into him, they react more or less as he hoped, with his mother immediately swearing her devotion to him:

Bueb, Bueb, was wosch usmer mache? Soll i öppe vor dr i d'Chneu falle? Soll i?—Ach.—I ha der großes, großes Unrächt ato. Aber i will's guet mache.

My boy, my boy, what are we going to do? Do I really need to fall to my knees before you? Do I? Oh, I have done you a great, great injustice. But I shall make it right.

Bleurgh. This maternal reconciliation scene becomes so florid that it edges into Oedipal territory, though perhaps I am misunderstanding things.

This particular edition, part of the appealing Insel-Bücherei series, is beautifully done, with some illustrative woodcuts and an afterword from someone at the Robert Walser Centre which makes a lot of rather grandiose claims for such a minor piece of juvenilia. There is also a translation of the text in Standard German, which was a big help to me at several points (though Swiss GR friend Isabelle says that in literary terms the German version is a disaster).

Basically it's forgettable; a nice curio for Walser fans at best, and one that can at least be read comfortably in under an hour. Though I'm afraid it took me more than a month armed with a shelf's worth of Schwiizertüütsch dictionaries.

‘Exterminate all the brutes!’ – Kurtz

A very readable summary of one of the first real international human rights campaigns, a campaign focussed on that vast slab of central Africa once owned, not by Belgium, but personally by the Belgian King. The Congo Free State was a handy microcosm of colonialism in its most extreme and polarised form: political control subsumed into corporate control, natural resources removed wholesale, local peoples dispossessed of their lands, their freedom, their lives. To ensure the speediest monetisation of the region's ivory and rubber, about half its population – some ten million people – was worked to death or otherwise killed. And things were no picnic for the other half.

Hochschild's readability, though, rests on a novelistic tendency to cast characters squarely as heroes or villains. Even physical descriptions and reported speech are heavily editorialised: Henry Morton Stanley ‘snorts’ or ‘explodes’, Leopold II ‘schemes’, while of photographs of the virtuous campaigner ED Morel, we are told that his ‘dark eyes blazed with indignation’. This stuff weakens rather than strengthens the arguments and I could have done without it. Similarly, frequent references to Stalin or the Holocaust leave a reader with the vague idea that Leopold was some kind of genocidal ogre; in fact, his interest was in profits, not genocide, and his attitude to the Congolese was not one of extermination but ‘merely’ one of complete unconcern.

Perhaps most unfortunate of all, the reliance on written records naturally foregrounds the colonial administrators and Western campaigners, and correspondingly – as Hochschild recognises in his afterword – ‘seems to diminish the centrality of the Congolese themselves’. This is not a problem one finds with David van Reybrouck's Congo: The Epic History of a People, where the treatment of the Free State is shorter but feels more balanced. (Van Reybrouck, incidentally, regards Hochschild's account as ‘very black and white’ and refers ambiguously to its ‘talent for generating dismay’.)

For all these problems, though, this is a book that succeeds brilliantly in its objective, which was to raise awareness of a period that was not being much discussed. It remains one of the few popular history books to have genuinely brought something out of the obscurity of academic journals and into widespread popular awareness, and it's often eye-opening in the details it uncovers about one of the most appalling chapters in colonial history. The success is deserved – it's a very emotional and necessary corrective to what Hochschild identifies as the ‘deliberate forgetting’ which so many colonial powers have, consciously or otherwise, taken part in.

An exquisite Edwardian oddity – a sort of magic-realist proto-campus-novel about paranoid sexual fantasy, as related by Beau Brummel or Oscar Wilde.

Our eponymous heroine is a personification of feminine desirability – ‘the toast of two hemispheres’, she has already, before the novel begins, ‘ranged in triumphal nomady’ around the capitals of Europe; Paris falls prostrate at her feet, Madrid throws a vast bullfight in her honour, the Grand Duke of Petersburg falls in love with her, and the Pope launches an ineffective Bull against her influence. Now, laden with innumerable jewels and dresses, she arrives in Oxford, where her powers seem to reach new heights. Soon, every undergraduate in the city is so obsessed with her that they all resolve to commit suicide in her name.

Zuleika herself is a strangely insubstantial creature, described at one point as ‘a vagrom breeze, warm and delicate, and in league with death’. She cares for nobody. At first, thinking that arch-dandy the Duke of Dorset is impervious to her charms, she falls violently in love with him; but when she discovers that he, too, is crazy for her, she goes off him at once. When men fight over her, instead of intervening she steps back, eyes dilating. The old truism about how over-interest is unattractive here finds unusually strong expression.

‘As soon as I grew used to the thought that they were going to die for me, I simply couldn't stand them. Poor boys! it was as much as I could do not to tell them I wished them dead already.’

There have been arguments over the polarity of Max Beerbohm's sexuality; I have to say, this would seem an unusual novel to write if you didn't have at least some interest in women, although certainly Zuleika Dobson represents a rather nervous and overawed (if very funny) view of them. Then again, perhaps he was gay as a window and the whole mass suicide thing is meant to be a satire on heterosexual relationships.

Either way, what makes this book such a total joy to read is Beerbohm's ornate, precise prose style, which allows him a mastery of various comic effects – irony, bathos, conversational wit. Objectionable characters are dismissed casually as being ‘odious with the worst abominations of perfumery’ (a phrase to steal), or in the case of one unfortunate individual,

looking like nothing as much as a gargoyle hewn by a drunken stone-mason for the adornment of a Methodist Chapel in one of the vilest suburbs of Leeds or Wigan.

Beerbohm can employ beautiful throwaway references to – for instance – ‘the ascending susurrus of a silk skirt’, but he can also launch into these gravely portentous ejaculations that I found unaccountably hilarious:

Aye, by all minerals we are mocked. Vegetables, yearly deciduous, are far more sympathetic.

Having spent all of my twenties compiling vast notebooks of vocabulary from my reading, it is rare now that a book teaches me any new words, but this one sent me gleefully to the dictionary to check such beauties as opetide or disseizin, and left me relishing such coinages as omnisubjugant, virguncule and commorients. Here is a writer with panache, and wit, and superb technical control – and, probably, some issues, but all the more reason to read him and enjoy him. How devastating that this was his only novel: it's a weird, unmissable delight.

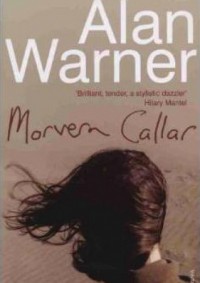

A lonely, beautiful novel whose narrative voice will wow you and unsettle you in equal measure. Morvern Callar is a twenty-one-year-old girl who works in a supermarket in a run-down Highlands port town (probably some version of Oban); she wakes one morning before Christmas to find that her boyfriend has killed himself in their apartment. The distant, carefully-described way she reacts to this event is, in a sense, at the heart of the novel's fascination, certainly its initial pull on the reader. Like someone from an Icelandic saga, she describes her actions but not her emotions; ‘a sort of feeling went across me’ is about the most we are ever given.

You might see her as numb or in shock; you might with equal justification find her psychotically detached. But she is riveting. By turns naïve and knowing, undereducated but sure of what she wants, her voice is direct, colloquial, dialectal, instantly believable.

It was a dead clear freezing day with bluish sky the silvery sun and you saw all breath.

Uninterested in art or literature (her dismissal of novels is one of the many ironies of this, a first novel), she is however encyclopaedic on contemporary dance music; the text is shot through with track titles and mixtape listings, and there are several hypnotic scenes in clubs that made me feel exhausted and about a hundred years old. When the book came out, Warner was pegged with Irvine Welsh as part of some imagined new wave of Scottish ‘rave novelists’ but, really, it's James Kelman's quotidian, Scots-inflected narrative voices that are the more obvious influence here.

The narrative voice in this case is amazingly unreflective for a novel, focused only on facts and descriptions. These come out in a patois all her own that makes heavy use of blurring suffixes like -ish and -y and nominalisations in -ness. ‘Stars were dished up across all bluey nighttimeness,’ she says, looking at the sky. But this idiom is still capable of all kinds of gentle insights:

I woke and felt queerish. I could tell it was nighttime by the type of voice on telly.

The ‘cross-writing’ in particular hasn't worked for everyone – Warner has been criticised in some quarters for lacking the skill, or even the moral right, to adopt the voice of a young woman. I don't agree, but I do think Morvern's obsession with her own anatomy, clothing and personal hygiene might lead you to guess that her author is a man. In some books this can be charming, but I confess here I did find it a little unsettling. Still, in general I would maintain that this kind of ‘appropriation’ or ‘colonisation’ is really the whole point of fiction, and it's certainly one of the central themes of this novel.

A film adaptation from Lynne Ramsay in 2002 did a great job of capturing the poetic beauty of the novel, but it committed the cardinal sin of making Morvern Callar English, which I couldn't understand – it's not just that you lose the Scottishness of the central voice, but that part of what the book seems to be about is quite specifically being Scottish, growing up there, leaving Scotland, how Scotland relates to Europe. These themes make it an appealing novel to revisit at the moment, though its qualities are likely to speak to you any time, anywhere.

And this despite the fact that Morvern Callar herself is rather a quiet presence in the book: another of its ironies is that her story can seem so articulate, and of something that could not be expressed in standard English, while she as a character is almost mute at times – numb with shock, overwhelmed by friends, silenced by society. ‘Callar,’ Morvern is told by a receptionist at a Spanish resort – ‘ah, it means, ah, silence, to say nothing, maybe.’ Maybe not.

1

1

Thérèse et Isabelle

In the mid-1950s, Violette Leduc wrote a novel called Ravages. The first hundred and fifty pages comprised a semi-autobiographical depiction of two schoolgirls in a torrid lesbian relationship, which Leduc said she hoped would be ‘no more shocking than Mme Bloom’. Yes they said Yes it is more shocking yes. Her publishers refused to print it, and the novel appeared without its opening section in 1955 (and did very well). Ten years later, a different publisher agreed to print the excised material as a stand-alone novella, although they still insisted on certain cuts for legality: this was the original 1966 form of Thérèse et Isabelle, the fully uncensored version of which did not appear in French until the year 2000, nearly thirty years after its author had died.

It is very explicit in places, but also deeply poetic. Leduc said her aim was to ‘render as minutely as possible the sensations experienced during physical love’ and while at times this feels like a slightly limited goal, she succeeds at it brilliantly. In terms of purely physical sensations, this short book contains the best sex scenes I've ever read. And yet they're not all that sexy – to me, anyway – because it is purely physical sensation: there is almost no emotional background, no build-up, no characterisation of either Thérèse or Isabelle that goes beyond each girl's overwhelming desire for the other.

Nevertheless the language is remarkable. Leduc has a tendency to come out with these gnomic, existential remarks, which don't always make perfect sense but which demand to be quoted for their sheer inventive pleasure:

La caresse est au frisson ce que le crépuscule est à l'éclair.

(The caress is to the shiver what dusk is to the lightning-bolt.)

Quand on aime on est toujours sur le quai d'une gare.

(When one is in love, one is eternally on a railway-station platform.)

Je la regarde comme je regarde la mer le soir quand je ne la vois plus.

(I watch her the way I watch the sea in the evening when I can no longer see it.)

Ma bouche rencontra so bouche comme la feuille morte la terre.

(My mouth met her mouth as a dead leaf meets the earth.)

J'entrais dans sa bouche comme on entre dans la guerre

(I entered her mouth the way you enter a war.)

At times these lapidary flourishes work very well; at other times, they topple over into high-flown nonsense (‘I was seized by the glove of infinity’, and much more in the same vein). There is also something a bit…oppressive about the tone for my tastes, with zero sense of humour and much earnestness. Admittedly these characters are only seventeen, and sex does tend to feel like the end of the world at that age, but still, wow!, talk about intense. Just hours after hooking up, Thérèse is already fantasizing about cutting off the hands of everyone else that touches her new lover, while Isabelle is raising the prospect of the two of them jumping off a cliff together so that neither outlives the other. It made me laugh because of the whole running joke in the LGBT world that gay women are super clingy super fast (you remember the classic gag: what does a lesbian bring to a second date? A U-Haul). At the same time I was impressed by it, just because of how few writers are attempting this sort of thing now.

I became fixated on the pronouns. They were still referring to each other by the formal vous until nearly halfway through the story! It was blowing my mind. You would think by the time you're knuckle-deep inside another person that one of you would have coughed politely and said, ‘Actually, do you mind if we tutoie each other?’ It's one of those little things that make me realise how much mental space is separating me from this world of 1950s provincial France.

All the more reason to experience it, though. The book is short and it builds, like a good quickie, to an intense and powerful climax where all of Leduc's characteristics work to best effect. An orgasm is captured in words like you would hardly believe possible (in a riot of synaesthesia: ‘my eyes heard, my ears saw’), and there are several more flashes of unexpected simile (Thérèse, trying to learn how to give oral sex, describes her gestures as feeling ‘like a scratched record repeating itself’ – this is fantastic).

For post-climactic comedown, Leduc leaves us with two final sentences that are the more devastating for being so simple after all the poetry that has gone before. It's a beautiful piece of work – limited in what it sets out to do, perhaps, and a little overblown at times, but nonetheless studded with frantic and extraordinary delights.

Talleyrand

Talleyrand was the greatest statesman of his age, and his age was one of the most dangerously eventful in Europe's history. Such was his renown as the archetypally cunning diplomat that when his death was reported in 1838, the reaction of Metternich, his Austrian counterpart, was: ‘I wonder what he meant by that?’

The story is probably apocryphal, but it's revealing. No one knew how to read Talleyrand, and history's verdict on the great man is still not in. Above all, he was a survivor: almost the only person to make it through France's numerous state shake-ups in one piece, from the French Revolution at the end of the eighteenth century, through the days of the Directorate and then the Consulate, the Napoleonic takeover and the proclamation of Empire, the Restoration of the Bourbons, and finally the July Monarchy in the 1830s. None of these regimes was known for its leniency towards predecessors, and yet Talleyrand didn't just survive every coup and revolution (he was behind several of them), he actually maintained a steady rise in power and influence.

So people cannot decide what to make of him. Either he was a brilliantly adaptable politician whose skills and experience made him impossible to ignore, even by those who would have liked to exclude him from power; or, he was the worst kind of opportunist – ‘a byword for tergiversation’, in Duff Cooper's wonderful phrase – who ditched his principles time and again in order to save his own skin.

This biography is broadly sympathetic – indeed when you read it, it's impossible not to like the man. No fan of hard work, Talleyrand looked down on younger, more zealous colleagues, and took the view that a diplomat's main job was to develop a refined sort of laziness and to excel in conversation. He was a product of that extraordinary French eighteenth century, when ‘such conversation as was then audible in Paris had never, perhaps, been heard since certain voices in Athens fell silent two thousand years before’. Talleyrand was always the wittiest and most intelligent man in any room. One contemporary describes him as

lounging nonchalantly on a sofa…his face unchanging and impenetrable, his hair powdered, talking little, sometimes putting in one subtle and mordant phrase, lighting up the conversation with a sparkling flash and then sinking back into his attitude of distinguished weariness and indifference.

He emerges from this book as a sort of aristocratic French Blackadder – witty, brilliant, dissolute, and quite prepared to be unprincipled if necessary. But this is unfair. Talleyrand may not have been willing to die for his principles – ‘nor even suffer serious inconvenience on their account’, as Cooper says – but he did have them. Cooper argues convincingly that there was a set of core beliefs to which he held throughout his whole career, beliefs which often made him unpopular with those in power. Prime among them were a desire for peace rather than conquest, and a commitment to constitutional monarchy. The former explains why he abandoned Napoleon. The latter is even more interesting, because it provides – if you're so minded – a justification for his other changes of allegiance: he supported the Revolution because the monarchy was not constitutional, and he supported the Restoration because the revolutionary government had shown that it did not have the ‘legitimacy’ of monarchy. (Hence his lifelong admiration for Britain, where he thought the perfect balance had been struck: a legitimate king whose power was held in check by a healthy parliament.)

All of this meant that he often acted for the interests of a peaceful Europe even when this ran counter to the wishes of the French government that he was currently serving. Sent by Napoleon to negotiate with Alexander I of Russia in 1806, Talleyrand simply told the tsar to refuse all of Napoleon's demands: ‘Sire, it is in your power to save Europe […] The French people are civilised, their sovereign is not. The sovereign of Russia is civilised and his people are not: the sovereign of Russia should therefore be the ally of the French people.’

Talleyrand was first published in 1932 and doubtless modern historians have moved the scholarship forward somewhat; nevertheless, it's very difficult to imagine this being done any better. Cooper writes beautifully, with a flair for efficient throwaway remarks of the kind modern historians shy away from now: he credits his readers with the intelligence to understand when he is speaking in generalisations for the sake of advancing an argument. He has a great turn of phrase, too. When Fanny Burney and her friends get to know Talleyrand during his exile in London, Cooper summarises the experience like this:

Prim little figures, they had wondered out of the sedate drawing-rooms of Sense and Sensibility and were in danger of losing themselves in the elegantly disordered alcoves of Les Liaisons dangereuses.

The idea cannot be captured more perfectly or economically. So I liked Talleyrand very much, and I liked Talleyrand very much too. He was the man still standing when the smoke cleared, the man not guided by stern morals but by practical genius and a love of the joys of civilisation that only peace can provide. ‘To the gospel of common sense he remained true.’ And although the few principles he did stick to were not always popular, they've become crucial to the Europe of today. Talleyrand may have played the long game, and enjoyed himself along the way, but in the final analysis he got it right.

The Faerie Queene

To me, this is the great long poem in English, beside which Paradise Lost seems like a clumsy haiku. Where Milton is precise and sententious, Spenser is exuberant, almost mad, and always focused on sheer reading pleasure. His aim is to take you on a crazed sword-and-sorcery epic, and his style combines godlike verbal inventiveness with the sort of eye for lurid details that an HBO commissioning editor would kill for.

It's almost like fan fiction. One imagines Spenser getting high over his copy of Malory one night, and then falling asleep and having a feverish opium dream about it. The Faerie Queene is the result: errant knights, evil witches and dragons, cross-dressing heroes, splenetic deities, and lots of damsels who get tied up in becomingly abbreviated outfits to await rescue. Despite this list of clichés, though, Spenser can also be fascinatingly transgressive, especially when it comes to gender roles: women in the Faerie Queene are by no means all passive weaklings, and there are no fewer than two different ‘warrior maids’ who ride around in full armour kicking the shit out of people who question their sense of agency or look at them funny. Note also the intriguing walk-on parts such as the giantess Argantè, who keeps men locked up ‘to serve her lust’ – a nice inversion of the usual trope of women being carted off as sexual prizes – and who is moreover defeated by the female knight Palladine.

Incidentally, Spenser likes to come up with inventive perversions to characterise his villains: Argantè is accused of prenatal incest, which I have to admit was a new one on me:

These twinnes, men say, (a thing far passing thought)

While in their mothers wombe enclosd they were,

Ere they into the lightsom world were brought,

In fleshly lust were mingled both yfere,

And in that monstrous wise did to the world appere.

I don't think enough has been written about Spenser's language. There is a tendency for modern readers to gloss over the tricky bits, and think: ‘Well, presumably this was an easy read back in the 1590s.’ It really wasn't. Spenser's language was, even to his contemporaries, extremely archaic and convoluted, with a distinct taste for inventive coinages. It's like a kind of Elizabethan Clockwork Orange (A Clockwork Potato?). Some of this is now invisible to modern readers. Words like amazement, amenable, bland, blatant, bouncing, centered, discontent, dismay, elope, formerly, gurgling, horrid, invulnerable, jovial, lawlessness, memorize, newsman, Olympic, pallid, red-handed, sarcasm, transfix, unassailable, violin, warmonger – all of them, and hundreds more, seem uncomplicated now, but that is only because Spenser invented them and we have become used to them in the centuries since. This is not to mention the hundreds of other words he coined that did not catch on and have now become obsolete (there's another).

I particularly like his flair for euphemism. Here's another awesome section, where a hapless husband has tracked down his wife after she was kidnapped by a group of satyrs. He hides nearby in the bushes, only to find out that she's actually having quite a good time:

At night, when all they went to sleepe, he vewd,

Whereas his louely wife emongst them lay,

Embraced of a Satyre rough and rude,

Who all the night did minde his ioyous play:

Nine times he heard him come aloft ere day,

That all his hart with gealosie did swell…

‘Come aloft’ of course meaning something along the lines of ‘mount sexually’. There's a lot of this kind of thing – Spenser not always coming across as the most secure guy in the world. The stanza concludes with another fun figurative flourish:

But yet that nights ensample did bewray,

That not for nought his wife them loued so well,

When one so oft a night did ring his matins bell.

Haha. Love it. This form of stanza – now known as ‘Spenserian’ – was his own creation, and the way each one concludes in a jaunty rhyming couplet makes him very quotable. I actually wrote this bit out in a notebook more than two years ago, which shows how long I've been reading this – it's been a sort of long-term project that I've dipped in and out of in between other books. This makes it hard to review, because I've now long forgotten half the stuff that happened in the first couple of sections. (Indeed when I started reading it, I was using a version on the internet, but I fell in love with the poem so hard that I ended up buying a luxury Folio Society limited edition bound in goatskin, probably the most expensive book in my entire collection – which, as Hannah was not slow to point out, seems hard to justify for a poem that you can read online for free.)

So OK, the paperback looks incredibly dull and imposing, and, yes, the idea of a 1500-page allegorical poem about Queen Elizabeth I does sound like a living nightmare – but The Faerie Queene is the opposite of boring. It's pure incident from start to finish. And if there's a message to the epic, taken as a whole, I think Spenser's closing lines point us in the right direction. He shows us that what matters in this world is not money or power – nor even, in the final analysis, the virtues that he has been exploring for nearly 40,000 lines. What matters is taking the time to find pleasure – in love, in knowledge, and, most of all, in literature:

Therefore do you, my rimes, keep better measure,

And seeke to please; that now is counted wise mens threasure.

Green Henry

As slow as a glacier and occasionally just as powerful, Green Henry is like your most stereotypical idea of the big, slow, earnest, nineteenth-century doorstop novel. A defining example of the Bildungsroman, it follows the life of the titular Henry from his childhood in Zurich through early adulthood and on to his abortive attempts to launch an artistic career in Germany. Germanophone countries still treat this novel as a mainstay of ‘Germanistic’ or German Studies courses, where students slog through it both for its importance to genre and as an example of so-called ‘provincial’ literature.

English speakers who want to enter into the debate can do so thanks to the rather dated AM Holt translation of 1960, which is published by Calder. The publishers aren't selling it very hard: the cover suggests an incredibly dull, set-text kind of book, and the lack of introduction or notes makes it seem even more stressfully big – it's literally just TEXT from front cover to back cover. If this was published by the NYRB, with an arty picture of an Alp on the front and some wanky introduction from Dave Eggers, it would have hundreds of ratings on here and an army of hipsters lining up to tell you why it's a neglected masterpiece. As it is, I feel the need to defend it, but it's certainly not easy.

When I was reading it, I was trying to think of other European writers with affinities to Keller and I was drawing a blank. Of English writers, the closest is probably Hardy – there is the same affectionate interest in the details of rural life, only with Keller things are much more painstaking and methodical. Ironically, the most enjoyable and interesting parts of the book for me were the faithful descriptions of daily Swiss life: a depiction of a country festival, where several villages stage a day-long semi-improvised production of William Tell, is a tour-de-force, and there is often a real documentary fascination in what we learn about the way people lived. I say ‘ironically’ because Keller famously disliked the French naturalists – for him, fiction was worthless if it was merely reportage, and hence his own bursts of naturalism are juxtaposed with more symbolic passages like dream sequences, in a blend that has become known to critics as ‘poetic realism’.

Whatever the genre, economy of expression is not one of Keller's gifts. The writing is dense, with almost no direct speech. Instead, there is a relentless internal dialogue whereby the narrator second-guesses every decision he makes. This analysis over whether to give money to a beggar is typical:

It has happened to me, to repulse a poor man on the street because, even while I wanted to give him something, I was thinking at the same time of God's approval, and did not want to act in my own self-interest. Then, however, I felt sorry for the poor man, I ran back; but while I was running back, my very compassion seemed to me too much of an affectation, I turned about once more; until the rational thought came to me: Be that as it may, the poor creature must have his due, that is the most important thing! But often this thought comes too late and the gift is not made…

If you're rolling your eyes over this and thinking, ‘Man, this guy really needs to get laid,’ then I believe you may be on to something. One of the other reviewers here points out that Henry doesn't manage to sleep with even one woman in more than seven hundred pages, and there is definitely a sense in which all this hyperanalytical fussiness starts to seem like redirected sexual frustration. Not so much Green Henry as Blue Balls. If Keller had been more like those French writers he mistrusted, and picked up a girl in the Palais-Royal aged thirteen, this book would have been very different, indeed might never have happened at all.

Actually, the women in here are surprisingly well-rounded and interesting characters, despite the fact that they are all put on a pedestal. In fact all the secondary characterisation is excellent; it's just the primary character who ends up being a bit annoying, which is quite a serious problem when you're spending seven hundred pages inside his head. There is a worrying sense, as you reach the end, that he hasn't really learnt anything at all, which makes the whole journey seem a bit pointless.

While I was reading this, my wife was reading another enormous book, The Quincunx. ‘It's so exciting!’ she kept saying. ‘They've just fled across the country – they're being chased by people who want to kill them. What's happening in yours?’

‘He just spent thirty pages deciding that maybe portrait painting is a truer expression of man's world-philosophy than landscape painting.’

‘Let's never swap.’

There are definitely powerful moments in Green Henry, but for me at least the interest dropped off sharply when he left Switzerland for Germany in the second half of the book. Pick it up by all means if you're interested in the time and place, but don't feel bad about dropping it when you get bored. Part of me wishes I'd done the same.

Dolores on the dotted line

Soon after I moved to Paris, I read an interesting article about Lolita in Le Monde which touched on some of the reaction the book had had in France. One particular photo intrigued me. It was from 5 July 1960 and showed a group of actresses protesting in front of the Académie Française – not about the book's content but about a linguistic point. Their banner reads:

NON MONSIEUR NABOKOV

NYMPHETTE

EST FRANÇAIS DEPUIS RONSAR

What they were so annoyed about was the fact that Nabokov claimed to have coined the word ‘nymphet’ for his novel. Not so for the French equivalent, the Académie's supporters insisted. (The Monde journalist, not a big Lolita fan, calls ‘nymphette’ a diminutif répugnant, on what appear to be moral rather than linguistic grounds.) The ‘Ronsar’ this banner refers to is Pierre de Ronsard, a member of the 16th-century Pléiade group of writers.

So I went out and bought a book of his verse in an attempt to find this point of vocabulary. Eventually, after about four and a half hours of reading in the Luxembourg Gardens, and with a rapidly developing appreciation for this poet, I finally found sonnet CXIV of the Amours. I'll just quote the relevant sestet:

Quand ma Nymphette en simple verdugade

Cueillant des fleurs, des raiz de son œillade

Essuya l'air grelleux & pluvieux,

Des ventz sortiz remprisonna les tropes,

Et ralenta les marteaux des Cyclopes,

Et de Jupin rasserena les yeulx.

Which is something like:

When my nymphet, in just her underwear,

goes picking flowers, her flirtatious stare

clears the rain and hail from above –

she returns the loosed wind's moan to peace

and makes the Cyclops' hammers cease,

and calms the eyes of Jove.

(This was before I had kids, and before Hannah had come out to join me in France. The idea of spending all day in the park reading Middle French poetry now is like the stuff of a madman's dream.)

Now to defend Nabokov, I'd point out that here the word is really used (albeit somewhat figuratively) in its general sense of ‘small or young nymph’, a sense in which it already existed in English. While the OED's entry does give Lolita as the earliest quotation for the sense of ‘sexually attractive young girl’, it also records several ‘small nymph’ citations going back to 1612. The earliest citation in French is from 1512, so arguably they could still win if it came to a stand-up fight about precedence.

Given Nabokov's predilection for dictionaries, I would say the odds are considerably against his not knowing all of the above. The more so when, as I later discovered, Ronsard is actually referenced in Lolita. Quoting Nabokov is always a delight, so:

I now refused to be diverted by the feeling of well-being that my walk had engendered – by the young summer breeze that enveloped the nape of my neck, the giving crunch of the damn gravel, the juicy tidbit I had sucked out at last from a hollowy tooth, and even the comfortable weight of my provisions which the general condition of my heart should not have allowed me to carry; but even that miserable pump of mine seemed to be working sweetly, and I felt adolori d'amoureuse langueur, to quote dear old Ronsard, as I reached the cottage where I had left my Dolores.

I thought it was rather brilliant of him to have found a Ronsard quote which puns on Lolita's name – but in the back of my Annotated Lolita I read: ‘The phrase “d'amoureuse langueur” appears several times, with slight variations, in Ronsard's Amours. “Adolori” […] is, of course, HH.'s addition.’

Of course.

Anyway: read some Ronsard. You mever know which postmodern novelist is going to appropriate his stuff next, and it's always good to be prepared.

Blasted

There have been three great shocks in post-war English theatre. The first was Edward Bond's Saved (1965), which features a baby being stoned to death on stage; the second was Howard Brenton's The Romans In Britain (1980), the first on-stage depiction of homosexual intercourse. Sarah Kane's Blasted was the third, and probably the most shocking of them all.

It premiered in 1995; I read it a couple of years later and although I was admittedly fairly young and impressionable, I still remember how numb and dazed I felt for about a week afterwards. A few months after that, in February 1999, newspapers reported that Sarah Kane had taken a deliberate overdose of prescription drugs. She was rushed to hospital in London and revived, but a few days later she managed to sneak away from her nurses' supervision and hanged herself with her shoelaces. She was 28.

Since then, it has become common to ascribe the extremes of her work to her troubled state of mind. Although there is certainly some truth in this, works like Blasted are in no way just therapeutic purging. She was a technically brilliant writer, and all her work shows a very incisive use of the theatre space and the possibilities of stagecraft – this is what makes her so powerful and so hard to ignore.

Blasted was her first full-length play, and the setting is a northern English town after society has broken down into civil war. As is usual with civil wars, this entails torture, sexual violence, rape, cannibalism and other brutality and Kane holds nothing back in putting across a certain form of horror with a particular kind of bleakly efficient scripting.

People have misinterpreted the obscenity of the play as deliberately far-fetched, a series of grotesqueries manufactured for shock value. Such people need to read more about Bosnia, or Rwanda. The brilliance of the play is precisely to make this stuff real by transposing it to Leeds.

There are only three characters – Cate, Ian and an unnamed Soldier. Most of the scenes are dialogues between two of them. The stage directions are astonishing in what they ask of the actors.

It is a play that shows human beings in their last resort, naked and shitting in fear, lashing out not because they are ‘evil’ or perverted but because they are utterly heartbroken and desperate.

I can feel that lick of despair in my stomach just remembering how some of this plays out. Although. And yet. It is not completely without all hope, either – indeed Caryl Churchill famously called the play ‘rather tender’.

Nevertheless, reviewers staggered out of the first production at the Royal Court white-faced in disbelief, and most followed the general line set by Jack Tinker in the Daily Mail:

Although he misses the whole point of the play, I like his opening: ‘Until last night I thought I was immune from shock in any theatre. I am not.’ As it happens, once people started to recover from the initial impact of the play, its qualities gradually became clearer, and by the time Kane committed suicide it was already being acknowledged by a lot of critics as something uniquely impressive. A revival in 2001 brought more understanding and admiring critical notices.

I've never seen it staged, and I'm not entirely sure I'd like to. Actually this is a difficult play to rate, because even if you admire it it's hard to feel affection towards it.

But once seen (or read), it's never forgotten, and it has loomed up in my mind many times since I first encountered it – both while covering conflict zones myself, and also just at home when reading the newspapers or listening to politicians. Blasted is out there, waiting for us. It stands for what we need to avoid at all costs.

Les Enfants terribles

When me and my sister were younger – like four and five, or five and six – we used to play these epic games in the back seat of our parents' car on long journeys. The car was a big old Citroën estate, like the vehicle from Ghostbusters, and the back seat folded down to form a huge play area (this was before anyone bothered about seat-belts in the back).

The games we played were incomprehensible to everyone but ourselves, and now we're older they've grown incomprehensible to us too. All I can remember are a few titles. One game was called ‘Baby in Australia’, which – bizarrely – was about a baby travelling around the United States having adventures. It was like Rugrats meets The Littlest Hobo. I'm not quite sure why we gave this such a confusing name. Another, more logically titled, game was called ‘Strongbaby’ (one word), and involved a baby with superhuman strength. I'm not certain now to what use an infant would really put Hulk-like strength, nor for that matter why we were both so obsessed with babies. But mothers and fathers reading this will readily appreciate that our own parents were happy to tolerate what appeared to be incipient psychological problems on the grounds that it kept us quiet for the length of a three-hour jaunt up the A1M.

I hadn't thought about this for years. Then I read Les Enfants terribles and it all came flooding back. If you've read the book this may sound alarming, but fortunately in our case it apparently never went further than a lot of weirdly regimented transport-based role-plays. For Paul and Élisabeth, the central characters of Cocteau's dark and dreamy novel, the shared world of childhood fantasy takes on a more all-consuming and sinister aspect.

Orphaned twins, they construct a haven of their own in their dead mother's apartment on the rue Montmartre (just round the corner from where I work), where their room is all low lighting, red textiles, pictures pinned up from newspapers, and a collection of hoarded ‘treasure’ brought back from the outside world. Here, in the middle of the night, the teenagers play what is only ever referred to as ‘the game’, a sort of never-ending psychological test of one-upmanship which governs their entire lives: the game is nothing less than a ‘semi-consciousness into which the children plunged’, which ‘dominated space and time; it initiated dreams, blended them with reality’.

Outsiders are brought into this private world, but they are always ultimately cat's-paws used by one sibling to get at the other. The self-imposed rituals are about domination, and there is a crackle of erotic charge everywhere: indeed at times this reads like the most literary treatment of D/S ever made. This is not to say that the book is about sex; it is much more oblique and remarkable than that. In one extraordinary scene, Élisabeth waits until Paul is just dropping off to sleep, and then, at three in the morning, she suddenly produces a bowl of crayfish from under her bed and starts eating them, ignoring Paul's anxious requests for her to share.

‘Gérard,’ [she says to Paul's schoolfriend who is with them,] ‘do you know of anything more depraved that some sixteen-year-old kid reduced to asking for a crayfish? He'd lick the rug, don't you know, he'd crawl on all fours. No! Don't give it to him, let him get up, let him come here! He's so vile, this great playboy who refuses to move, dying for nice food but not able to make the effort. It's because I'm ashamed for him that I'm refusing to give him a crayfish….’

[—Gérard, connaissez-vous une chose plus abjecte qu'un type de seize ans qui s'abaisse à demander une écrevisse? Il lécherait la carpette, vous savez, il marcherait à quatre pattes. Non ! ne la lui portez pas, qu'il se lève, qu'il vienne ! C'est trop infecte, à la fin, cette grande bringue qui refuse de bouger, qui crève de gourmandise et qui ne peut pas faire un effort. C'est parce que j'ai honte pour lui que je lui refuse une écrevisse….]

An hour later, when Paul finally gives up and goes to sleep, Élisabeth wakes him and forces him to eat the crayfish, ‘breaking the carapace, pushing the flesh between his teeth’ as Paul struggles to chew while half-asleep: ‘grave, patient, hunched over, she resembled a madwoman force-feeding a dead child.’

It's an incredible scene the like of which I've never read anywhere else, and all described in this beautiful, verbally rich, precise Coctellian prose. The oppressive and erotic atmosphere is picked up on later by one of Élisabeth's friends, who is pining submissively after Paul: she ‘thrilled to be a victim because she felt the room to be full of an amorous electricity whose most brutal shocks were made inoffensive’. The novel's dénouement is going to prove her horribly wrong on this point.

The conclusion is dark and very French: the quasi-incestuous power-play cannot survive impact with adulthood, and implodes with considerable collateral damage. But how difficult for a writer to enter into this private world of childhood fantasy, and how perfectly Cocteau pulls it off. Some of his lines froze me with horrified delight: when the children find their mother dead in her room, the body is described as a ‘petrified scream’ – ‘ce Voltaire furieux qu'ils ne connaissent pas’. He combines the eye of a poet with a good novelist's willingness to examine the psychic areas usually left unexamined.

This year marks fifty years since Cocteau's death, and it's a good excuse to try him out if you haven't yet (as I hadn't until recently). Reading this is like having a beautiful dream that modulates into a beautiful nightmare. I kind of want to send a copy to my own sister, but I can't help feeling like that might be in bad taste.

The Physicists

The fact is, there's nothing more scandalous than a miracle in the realm of science.

Three of history's greatest physicists meet in a drawing-room: Newton, Einstein and Möbius. Newton has a bottle of cognac hidden in the fireplace. Einstein has just strangled a woman to death. And Möbius is being visited by the ghost of King Solomon, who is telling him the secrets of a Unified Field Theory.

Except the drawing-room belongs to a Swiss insane asylum, and the three men are patients.

What follows is a playful mash-up of a country-house murder-mystery with a scientific drama-of-ideas. At first the execution reminded me of Tom Stoppard – high praise round my way, because I think Stoppard's one of the greatest writers alive. But while Stoppard's work is always discursive, and never tries to convince you of a particular position, Dürrenmatt takes a more polemic approach here – especially in the second act, where the characters are increasingly fixated on the dangers of scientific discoveries falling into the wrong hands.

She considered me an unrecognized genius. She didn't realize that today it is the duty of a genius to remain unrecognized.

Great line. Of course when this was first performed in 1962, the Cold War was still on and this felt more of a live issue. It was less than 20 years since the real Einstein had famously said that if he'd known what the results of nuclear research would be, he would have become a watchmaker. (He also said, ‘The discovery of nuclear chain reactions need not bring about the destruction of mankind any more than did the discovery of matches,’ but no one remembers that one.)

These are still crucial questions, but I think the sophistication of the debate has slightly overtaken the moral of this play. Nevertheless, there is a huge amount of fun and intellectual enjoyment to be had here, with jokes and theories and interesting dramatic ideas on every page. I'd love to see it staged – but if waiting for your local theatre to get on board seems daunting, the ideas involved make this well worth reading in the meantime.

4

4

2

2

Bruges-la-Morte

I sometimes get the worrying feeling that nineteenth-century men preferred their women to be dead than alive. There is something archetypal about the repeated vision of the pale, beautiful, fragile, utterly feminine corpse. Beyond corruption, a woman who's died is a woman you can safely worship without any danger that she'll ruin the image by doing something vulgar like using the wrong form of address to a bishop, or blowing your best friend. It's a vision that crops up everywhere in the works of these fin-de-siècle writers, who were unhealthily obsessed with Edgar Allen Poe and with the figure of drowned Ophelia (for them, more Millais than Shakespeare).

Bruges-la-Morte (1892) is the apotheosis of this kind of preoccupation. As my introductory para suggests, I find the general mindset a little problematic, but this is certainly a beautifully-written distillation of the theme. Hugues Viane, our melancholy hero, settles in Bruges after the death of his wife, and prepares to live out the rest of his days nursing his memories of her: he dedicates a room of his house to her portraits, and preserves a lock of her hair in a glass cabinet.

When he's not staring at her pictures, he's out taking moody walks along the canals.

Where, one day, he sees a woman in the street who looks identical, in every detail, to his dead wife. Is it a ghost? An appalling coincidence? His mind playing tricks on him?

And might it be somehow possible to recreate his lost love…?

Viane is the main character; but drizzly, grey Bruges is the real hero of the book. The city is portrayed as the necessary complement to Viane's feelings of loneliness:

Une équation mystérieuse s'établissait. À l'épouse morte devait correspondre une ville morte.

[A mysterious equation established itself. To the dead wife there must correspond a dead town.]

The point is underlined by the inclusion of a number of black-and-white photographs of the city, looking still and silent, and often including unidentified figures. A modern reader can't help seeing the effect as Sebaldian.

But anyway, however interesting this early use of photography may be, the real star is Rodenbach's prose. He finds a thickly atrabilious style to fit his story, rich in imagery, full of strikingly depressive turns of phrase. The city's canals are ‘cold arteries’ where ‘the great pulse of the sea has stopped beating’; the famous Tour des Halles ‘defends itself against the invading night with the gold shield of its sundial’; down below there are streetlamps ‘whose wounds bleed into the darkness’.

This must be what people mean when they talk about ‘prose-poetry’. There are some paragraphs here that seem to be made up entirely of alexandrines. And then just look at a phrase like this:

Les hautes tours dans leurs frocs de pierre partout allongent leur ombre.

There is a progression of vowels here that slides forward through the mouth beautifully, ending with the wonderful dirge-like assonance of allongent and ombre; and the consonants travel too, from the silent h of haut, back in the throat, forward to the t of tours, on to one lip with the f of frocs, then both lips for the two ps, and finally the lips are pushed right out for the last two nasal vowels. Wowzer! (Translation: something like: ‘Everywhere the high towers in their stony habits stretch forth their shadow.’)

Earlier this year I read Nerval's Les Filles du feu, and I kept being reminded of it while I was reading Bruges-la-Morte. There is exactly the same fascination with the ‘doubling’ of a love interest: one woman becomes two (or more), each taking on different attributes – one is blonde, the other dark, one is pure, the other degraded, one is a virgin the other is a whore, and so on. Some scenes, some lines, are almost identical: Rodenbach must surely have been a Nerval fan. He sums up the poetic essence of this tradition perfectly – indeed so perfectly that I found the formalities of plot resolution at the end of the book to be irritatingly drab and melodramatic by contrast. I guess that's the problem with turning poetry into a novel.

Nevertheless, Bruges-la-Morte is obviously a high point of Symbolist writing, a book that's obsessed with death and always alert to new ways to externalise deep emotions. There is a brooding openness to the supernatural, and a looming architectural presence, which also has clear links with the Gothic. But more importantly it's just beautifully-written: every sentence drops balanced and gorgeous into your head.

For best results, it should be read at dusk, preferably when it's raining outside. Just make sure you have a brisk walk afterwards.

5

5

4

4

Blood & Guts

This is one of those ‘surrogate’ books – I bought it because I really wanted something else, so any disappointment is my own fault.

The book I wanted was Porter's The Greatest Benefit to Mankind, his mammoth tome on the history of medicine, but my friendly neighbourhood bookshops never seem to have it when I'm in the mood. Instead, I bought this, which I thought might tide me over.

To be fair, the clue is in the title. This history of medicine really is short – if you take off the notes, bibliography and the many full-page illustrations, you're left with barely 150 pages of text. (Edit: I just counted, it's actually 130.) Like a literary amuse-bouche, I thought it might whet my appetite for the bigger version (excuse the dangling modifier), but despite the clear labelling I unfortunately found it more frustrating than stimulating.

The approach is thematic: eight chapters, each dealing with a different aspect of medicine, including disease itself, anatomy, surgery, the hospital, and so on. So we have a score of pages on each, running very briskly from antiquity to now, before resetting the clock again at the start of the next chapter. Porter's prose is as wonderful as ever, and his conclusions typically judicious. But the frenetic pace doesn't show off his talents to best effect, and the merciless effort to pare things down to the essentials means there's little room for all the grisly anecdotes of mediaeval births and eighteenth-century amputations that you want from something like this.

My preconceptions aside, this is a solid grounding in the story so far, and it will bring you up to speed. It will also have you thanking all the gods, once again, that you were born in the era of anaesthetics and antibiotics (although, as always, you can't help wondering what future generations will consider appalling about our own time).

It has some interesting things to say about modern medicine too, especially the drive towards healthcare-as-business in the US: I was amazed to read that one head of the Hospital Corporation of America was a former fast-food manager who said approvingly that ‘the growth potential in hospitals is unlimited: it's even better than Kentucky Fried Chicken’. ‘In the USA health insurance became a lasting political football,’ Porter comments mildly in 2002. (Oh Roy, if you only knew.)

‘Compulsory Health Insurance,’ declared one Brooklyn physician, ‘is an Un-American, Unsafe, Uneconomic, Unscientific, Unfair and Unscrupulous type of Legislation supported by…Misguided Clergymen and Hysterical Women.’

Porter is surprisingly ambivalent when it comes to giving an overall verdict on modern medicine, taking the view that improvements in life expectancy and pain relief are offset by commercialisation and a dubious record in how well western techniques have been exported to the developing world. (That is, investing in basic hygiene and nutrition might have been better than exporting expensive pharmaceuticals.)

I can't give this less than three stars, because the facts are all there and he writes beautifully. Unfortunately, the fact is that I wanted a lobster thermidore and I ended up nibbling a breadstick.

How Amazon and Goodreads could lose their best readers

Check out the article, mentioning our own wonderful Ceridwen!

The first article by the same author got a lot wrong. This time, while I don't exactly agree with everything that's been said, I think it's a lot more balanced, which is really all that I expect from a journalist.

So, awesome that the article exists, but I'm confident that it isn't going to change Goodreads' policy changes (or ham-fisted implementation style).

1

1